This is the second of five installments of Chapter Two of The Last War in Albion. The entirety of chapters one and two are available as an ebook single at Amazon, Amazon UK, and Smashwords. Please consider helping support this project by buying a copy.

PREVIOUSLY IN THE LAST WAR IN ALBION: In 1979, Grant Morrison began writing and drawing Captain Clyde for The Govan Press, a small local paper of a district in Glasgow. The comic attempted to depict a quasi-realistic local superhero, named after the River Clyde upon which Glasgow sits, who, like Morrison, was just an unemployed Glaswegian trying to get by. Installments of Captain Clyde are extremely difficult to locate, but several strips are publicly available…

“A society where nothing can change because it takes superhuman effort to keep things the way they are.” - Warren Ellis, 1999

|

| Figure 48: The goddess Elen offers Chris Melville superpowers in an early installment of Captain Clyde (c. 1979) |

The first strip appears to be from the earliest days of the strip - a plot that O’Donnell describes summarises as Melville being “offered the powers of Earth and Fire by the earth goddess Elen - If he could defeat her champion, Magna.” This, Morrison explains in response, is because of “an interest in ley lines and earth magic and all that pseudo mystical, hippy shit,” marking the first documented instance of Morrison’s fascination with magic and the occult. Morrison reiterates this in Supergods, using the story of his uncle giving him the Aleister Crowley/Frieda Harris Thoth Tarot for his nineteenth birthday, which got him into magic as a bridge between his discussion of Chris Claremont’s run on the X-Men and his own Captain Clyde work. The anecdote culminates with him performing what he describes as “a traditional ritual” resulting in “a blazing, angelic lion

|

Figure 49: Lady Frieda Harris's design for The Magus (aka The Magician) in Crowley's Thoth Tarot |

head… growling out the words “I am neither North nor South.” The second strip at least somewhat continues on that theme, showing Captain Clyde collapsed at the center of a stone circle before being renewed by some mystical power. This strip does not seem to immediately follow from the first, as Melville is identified by the caption box as Captain Clyde, suggesting it is not the origin story. Instead it appears to illustrate a feature of Captain Clyde, who, as Morrison puts it, “periodically has to recharge his powers by drawing earth energy from standing stones and other sacred sites.” The interest in Scotland’s otherness and pagan roots reinforces the initial sense of Captain Clyde as a sort of dissident superhero strip - an attempt to recreate the concept from the outsider perspective of an unemployed Glaswegian.

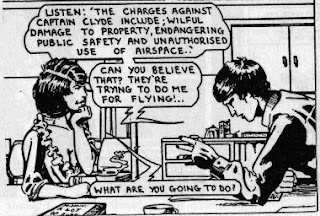

The other two strips are consecutive, and feature a battle between Captain Clyde and a villain named Quasar, who is described in Supergods as “a tweed-jacketed headmasterly villain” who turns into a “star-powered monster.” The chronology given in Supergods suggests this too is from the earlier portion of the strip, before its turn towards excess. This earlier portion is also presumably home to several of the smaller excerpts, which focus on the high concept “unemployed Glaswegian bloke as superhero” concept. These consist of Melville kvetching, both to himself and others, about the put-upon nature of his life. Other panels illustrate Morrison’s professed favorite of his villains, a character named Trinity who, as Morrison describes him, “was a schizophrenic with a triple personality who was able to divide his body into

.jpg) |

Figure 50: The unemployed Chris Melville complains about his hard knock life |

three - each with a different power and facet of the personality.” Another illustrates the Sinister Circle, which O’Donnell admits he considers Captain Clyde’s “finest hour.”

The remaining illustrations seem to be from the later period of Captain Clyde, which Morrison described in 1985 as “very grim and unpleasant” and “full of nasty deaths and evil forces” due to his having completely given up on any belief that anyone was actually reading his comic. In Supergods he describes the final arc as involving Captain Clyde being the victim of “full-scale demonic possession,” becoming the “self-proclaimed ‘Black Messiah,” and finally being “redeemed by Alison’s unswerving devotion” and killing the Devil itself before dying in a “rain-soaked, lightning-wracked epic of Fall and Redemption.” This is probably at least somewhat tongue in cheek, given Morrison’s 1985 admission that the story “was compressed into eleven episodes from the thirty or so I’d originally planned.” These strips are more

|

Figure 51: The terrifying visage of the Black Messiah |

poorly represented in the Fusion interview. The panels in which Melville succumbs to his Black Messiah persona are represented, but the precise details of a sequence in which a villain named Belphegor summons a fire elemental named Surtr are more obscure, as is a sequence in which a character prophetically talks about “a taste of dread on the wind… as though the end of all things draws near.” The tone suggests the demon-inflected later years of Captain Clyde, but even this is speculative.

And that’s about what can be discerned about Captain Clyde. It is in many ways the most important of the poorly documented incidents in the war. Morrison, for his part, is open in boasting about the strip due, one suspects, largely to the fact that it allows him to claim victory in a priority dispute with Alan Moore. Morrison cheekily presents Moore’s seminal work on Marvelman as “the next stage beyond the kitchen sink naturalism of Captain Clyde,” a claim that couples with his frequent suggestion that Moore’s Marvelman work inspired him to get back into comics. Morrison also, in late 80s/early 90s interviews, cites Captain Clyde as a sort of trial run for his major contribution to 2000 A.D., Zenith, a strip Morrison also presents explicitly as a reaction to Alan Moore.

|

| Figure 52: The naval base in Faslane |

This illustrates a key and in many ways inscrutable feature of the War, which is that a vast amount of it takes place around a topic that can only be described as idiosyncratic: the superhero. The superhero was not in and of itself big in the UK - certainly not in the same way that, for instance, 2000 AD or Eagle were. American superhero comics, on the other hand, were for a crucial period quite popular, albeit for idiosyncratic reasons. The usual story, which is perhaps more folklore than sound economic analysis, is that copies of American superhero comics in excess of what sold in America were repurposed as ballast for trans-Atlantic shipping. Once they were in the UK they were typically sold off as an afterthought, entering the markets through idiosyncratic distribution at cut-rate prices. (Interestingly, Morrison has suggested that the nearby American submarine bases in Faslane and Holy Loch meant that American comics were particularly likely to be available in Glasgow, claiming that the Yankee Book Store in Paisley was the first store in the UK to stock them.)

That’s in print, at least. On television, as the commissioning of Captain Clyde demonstrates, the Adam West-fronted Batman television series was a perennial bit of televisual ballast. So while the idea of the superhero was well known, it was firmly an imported concept. The only British superhero

|

Figure 53: Mick Angelo's Marvelman, essentially the lone significant British superhero |

of any significant note was Mick Angelo’s Marvelman, who, by 1979, had not been published in sixteen years, and even he was just a cheat to work around the consequences of the National Comics Publications v. Fawcett Publications debacle. Superheroes were an American thing that some British children enjoyed alongside the existing selection of British comics.

Among these British children, however, were both Grant Morrison and Alan Moore, a detail upon which the entire War hinges. This cannot be stated unequivocally enough - without both of their loves for American superhero comics, none of this would ever have happened. In this regard, being asked to write Captain Clyde was a huge deal for Morrison, who had been designing superheroes since his teens. But it is also worth stressing the degree to which its genre further places Captain Clyde outside any mainstream conception of the British comics industry of its time.

Still, it is worth discussing the superhero, both for its later influence upon the War and to provide a broader context for Morrison’s early work. The superhero is generally considered to have been invented by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster in 1938 for Action Comics #1, which was headlined with the first appearance of Superman. On one level this is unequivocally true and the only sensible understanding of the origin of superheroes. Certainly this is the origin story Grant Morrison used in Supergods, his at times compelling and at times maddening history of the superhero, which he opens with the

|

Figure 54: Cover of Action Comics #1, usually considered the first superhero comic |

text of the Superman Code. And it makes sense - Superman was the first of DC Comics’s wave of superheroes, followed quickly by Batman, Wonder Woman, and the first versions of the Flash, Green Lantern, and other heroes. The basic paradigm copied tentatively by one of their rivals, Timely Comics, which quickly churned out the Sub-Mariner (by Bill Everett, who is often claimed to have descended from William Blake, a misleading claim given that Blake had no children, although he is a distant relative), the Human Torch, and Captain America.

Superhero comics were popular in World War II, then declined, with Timely (by then Atlas Comics) cancelling all of its superheroes, and DC whittling its roster down to Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman - still treated as the nominal Holy Trinity of DC’s superhero line. But in the 1950s a team of DC editors and writers including Julius Schwartz, Gardner Fox, Carmine Infantino, Robert Kanigher, and John Broome created Barry Allen, a new version of World War II-era superhero the Flash, kicking off the Silver Age of American superhero comics. Atlas, once again followed suit, but this time hit on massive success with what is now the Marvel Universe, featuring the Fantastic Four, the X-Men, Iron Man, Thor, Spider-Man, and a revamped Captain America. The history of superheroes from there to the present day is relatively easy to infer the broad strokes of, and relevant details can be left for later.

|

| Figure 55: Doc Savage, a prototype of Siegel and Shuster's idea of the superhero |

Upon closer inspection, however, the release of Action Comics #1 is not quite the sui generis debut of the superhero that it might appear. Superman clearly fits into a tradition of masked crimefighters like Zorro, the Green Hornet, and the Shadow, who are themselves subsets of a larger category of pulp heroes including Doc Savage, John Carter, and Conan the Barbarian. Superman is original inasmuch as he’s both costumed and superpowered. But it’s impossible to create a definition out of these two facts. Costumes alone fail to distinguish the post-Superman characters from the pre-Superman ones. But equally, Powers are not a requirement of the post-Superman ones, nor absent from the pre-Superman ones. The second step in the standard history of superheroes, Batman, has no powers and is essentially indistinguishable from the Green Hornet or the Shadow, save for the fact that he happened to debut after Superman. And while nothing on quite the scale of Superman’s powers existed, there’s not a sizable difference between Superman’s powers and Doc Savage’s training since birth to be the absolute theoretical peak of human ability. Yes, Superman is an alien, but the situation is visibly just the reverse of Edgar Rice Burroughs’s John Carter, who has vast physical abilities when transported to Mars because his body is better adapted to the planet. Jerry Siegel even admits to the inspiration, and his powers were far less impressive in the early days than they are now. Even absolutely demanding the fantastic origin of the powers doesn’t work - the Shadow, when transported to radio, had what were blatantly supernatural powers.

|

| Figure 56: Many consider the costume to be a fundamental aspect of Superman |

So neither costumes nor powers are original to Siegel and Shuster. Nor is the idea of combining them adequate to explain the invention of superheroes. Costumes are not sufficient to define superheroes, and powers are not necessary. Whatever the idea of the superhero is, it resists a straightforward definition that links it inextricably to Superman. It is, however, telling that superheroes are inexorably associated with one particular medium: comic books. This separates them from almost any other popular genre, and suggests a more useful way of isolating them from adjacent genres. Superheroes have a visual dimension. This is also not an absolute rule - Batman and Superman both had radio shows, and novels like Robert Mayer’s Superfolks clearly featured superheroes despite not being illustrated.

For the purposes of understanding the War, however, an absolute rule that can be used to separate superheroes from non-superheroes is less useful than an explanation of why the terrian is how it is. Clearly the publication of Action Comics #1 was a landmark event in the development of superheroes. It defines the terrain upon which much of the War is fought. What matters is not what the terrain looks like, nor even what precise creative decisions caused it to look that way, but rather a larger question: why is this terrain worth fighting over? The answer to that question, at least, can be understood straightforwardly through the visual.

|

| Figure 57: Joe Shuster's frenetic art style put the "action" in Action Comics (Action Comics #1, 1938) |

What Action Comics #1 indisputably was is the first massively successful attempt at the pulp hero to be defined by colorful visual representation. Technologically speaking, this was not popular until cheap four-colour printing was possible. Accordingly, it was in 1930s comic books that it happened. The cleverness of Superman was that he used color well. He was bright - even lurid, and Siegel and Shuster had what was, for the time, a shockingly kinetic style of visual storytelling. What was crucial was not the idea of a costumed hero with special powers, but the fact that this particular costumed hero was interesting because he looked good. Grant Morrison tacitly confirms as much in Supergods, spending pages analyzing the visual composition of the cover of Action Comics #1, writing in ecstatic tones of “the vivid yellow background with a jagged corona of red” in its background and linking its visual design to “the gateway of the loa (or spirit) Legba, another manifestation of the ‘god’ known variously as Mercury, Thoth, Ganesh, Odin, or Ogma,” the latter being, predictably, a figure from the Cath Maighe Tuireadh, a ninth century celtic text.

The superhero is thus best used to describe a type of pulp hero story that emerged out of 1930s American comic books. Not all superheroes have their origins in comic books, but enough do that it is a reasonably entertaining game to identify ones who first appeared in another medium, particularly ones that have any degree of popularity today. They are defined primarily by a visual intensity and a sense of heritage tracing back to Action Comics #1. And they are worth fighting over because pulp heroes of that sort are a large part of contemporary culture, and have come to almost completely dominate the American comic book industry, in which large swaths of the War are fought.

But the War starts in Britain and remains, in the end, fought in Albion. And in British comics culture superheroes never gained the absolute dominance over the comics industry that they did in America. [continued]