This is the fifth of twenty-two parts of Chapter Eight of The Last War in Albion, focusing on Alan Moore's run on Swamp Thing. An omnibus of all twenty-two parts can be purchased at Smashwords. If you purchased serialization via the Kickstarter, check your Kickstarter messages for a free download code.

The stories discussed in this chapter are currently available in six volumes. The first volume is available in the US here, and the UK here. Finding volume 2-6 are, for now, left as an exercise for the reader, although I will update these links as the narrative gets to those issues.

And so the American revolution breaks out, overthrowing the chains of Urizen. At first glance, given Blake’s larger ideological predispositions, this ends triumphantly, with Orc’s fire threatens to engulf Europe as well. As European countries try “to shut the five gates of their law-built heaven / Filled with blasting fancies and with mildews of despair / With fierce disease and lust, unable to stem the fires of Orc; / But the five gates were consum’d, & their bolts and hinges melted / And the fierce flames burnt round the heavens, & round the abodes of men,” presaging the second of Blake’s continental prophecies, Europe a Prophecy. And yet beneath the surface all is clearly not well in the world. As the poem draws to its conclusion, the images turn dark and sinister, with scenes of despair and suffering. And for all the revolution’s lofty ideals, the description given is hardly encouraging. “Fury! rage! madness! in a wind swept through America / And the red flames of Orc that folded roaring fierce around / The angry shores, and the fierce rushing of th’ inhabitants together; / The citizens of New-York close their books& lock their chests; / The mariners of Boston drop their anchors and unlade; / The scribe of Pennsylvania casts his pen upon the earth; / The builder of Virginia throws his hammer down in fear. / Then had America been lost,” Blake writes, and it becomes all too clear that the revolution is not straightforwardly a good thing.

In practice, this reflects Blake’s steady rejection of the idea of a charismatic, leader-driven revolution, viewing that as, in the end, a reiteration of the underlying problem of Urizen and his egotistical desire to control. Ultimately, for Blake, a revolution based on authority is doomed to failure. And so the monstrosity of Orc becomes a strangely ambivalent thing, simultaneously doomed to failure and necessary for the world. A similar ambivalence pervades Moore’s story. At the climax, when the simian fear monster and another monster battle within the school, Swamp Thing tells Abby to take the child whose fear the Monkey King is feeding upon and flee to the swamp. Abby protests, asking “what about you? There are those two monsters, and…,” but Swamp Thing interrupts her, proclaiming, icily, “three Monsters.” The point being that Swamp Thing is a monster himself, a fact that casts the arc’s initial declaration that the sleep of reason produces monsters in a new and different light.

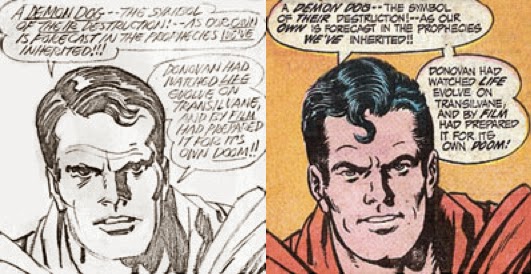

Upon arrival at DC, Kirby was given leave to create an expansive set of concepts and books generally referred to as the Fourth World saga. With covers proudly boasting “Kirby is here!” the series spoke volumes about the clout and acclaim Kirby had within the industry. But under the hood, the comics also revealed how strange a place DC was at the time. For all their evinced pride at having hired Kirby, they also were having every single drawing of Superman he did for his work on Superman’s Pal Jimmy Olsen (which he took on to fulfill DC’s request that he work on at least one existing title) redrawn by artists like Al Plastino, a late forties Superman artist who wasn’t even doing other work for DC, much to Kirby’s chagrin. And so when the Fourth World books did not generate the sales DC had hoped from their new star artist, they quickly (and again to his chagrin) moved him to other titles.

The first among these was a request that Kirby create a horror title for them. This was not a natural fit for Kirby or an assignment he was enthused about, but Kirby obliged, creating a book called The Demon that debuted in June of 1972, two months before Wein and Wrightson’s Swamp Thing #1. Etrigan was originally a demonic servant of Merlin tasked at the fall of Camelot to protect a portion of an ancient magical tome. After the fall, Etrigan turned to human form and lived for centuries under the name of Jason Blood, although with clouded memories that kept him from realizing his immortality. Eventually, however, Blood is lured to the crypt of a mysterious castle where he discovers an inscription reading “Change! Change, o’ form of man! / Release the might from fleshy mire! / Boil the blood in heart of fire! / Gone! Gone! - The form of Man! / Rise, the demon Etrigan!” This transforms Blood at last back into the demonic Etrigan, just in time to fight off Morgan le Fay, who has been pursuing him since the fall of Camelot to learn its secrets. From there Jason Blood and Etrigan proceed to have a fraught relationship in which Blood simultaneously fears and relies upon Etrigan’s power as they investigate and stop various supernatural goings on. The series ran for sixteen issues before it too was cancelled, and Kirby continued to float around DC for a bit doing odd jobs and creating more characters before finally getting frustrated and returning to Marvel at the end of his contract.

It is perhaps unsurprising, then, that the most vibrant component of Moore’s second arc is Moore’s treatment of Etrigan. Certainly it’s one of the elements Moore took the most care with. He describes in one interview how, in writing the character, “I settled myself down in front of a mirror and I closed the blinds so the neighbors didn’t see or become suspicious and phone the police or anything” and then begin a sort of acting exercise to figure out how the character would talk, hunching over and imagining himself talking through large fangs, with a speech impediment, and figuring out what that sort of speech would sound like. Combining this with an innovation introduced a few months earlier by a Len Wein-penned issue of DC Comics Presents whereby Etrigan’s speech was all delivered in rhyming couplets (as opposed to just his iconic “Change! Change o form of man” speech and one or two other rhyming couplets Kirby threw in), so that Etrigan’s first appearance in the second issue of the storyline opens with an extended monologue in sonnet form: “The toys about the nursery are set, for idiot chaos to arrange at whim. He drools and ruins lives, his chin is wet and old or young, it matters not to him. The gracious lady and her root-choked beast have come to save the innocents from harm, to spare them from the monkey’s dreadful feast. What noble souls they have! What charm! [continued]

The stories discussed in this chapter are currently available in six volumes. The first volume is available in the US here, and the UK here. Finding volume 2-6 are, for now, left as an exercise for the reader, although I will update these links as the narrative gets to those issues.

Previously in The Last War in Albion: Alan Moore's first arc on Swamp Thing was a massive success, and DC immediately began a new promotional campaign for the book. Moore, Bissette, and Totleben, meanwhile, moved on to their second arc, the first issue of which drew its title by a print by Francesco Goya called "The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters." This print shares thematic ground with the work of Goya's British contemporary William Blake, who wrote of Ahania, the female emanation of the mad god Urizen, who represents a higher form of intellect than the monstrous attempt to condemn the world to single vision. In Blake's The Foar Zoas, Ahania was separated from Urizen and fell into a slumber, until eventually Ahania cast off her death clothes.

"It's where Darkseid fell through existence to his doom. Leaving hell deserted. And there, in his absence, the first flower grew. So begins the myth of a new creation. Apokolips reborn as New Genesis." - Grant Morrison

She folded them up in care in silence & her brightening limbs / Bathd in the clear spring of the rock then from her darksom cave / Issud in majesty divine Urizen rose up from his couch / On wings of tenfold joy clapping his hands his feet his radiant wings / In the immense as when the Sun dances upon the mountains / A shout of jubilee in lovely notes responding from daughter to daughter / From son to Son as if the Stars beaming innumerable / Thro night should sing soft warbling filling Earth & heaven / And bright Ahania took her seat by Urizen in songs & joy.” For both Goya and Blake, in other words, some sense of balance is required - it is just that Goya fears the passions of man running unchecked, while Blake fears the prison of law and religion weaved by reason.

|

| Figure 414: Sullen fires glowing across the Atlantic to America's shore. (America a Prophecy Copy A, Object 5, written 1793, printed 1795) |

And in another sense, Blake is closer still to Goya, on an almost literal level. It is, after all, once Urizen has been bound by Los, the fallen, human form of Urizen’s opposite number, Urthona, that Los’s emanation, Enitharmon, is split from him and gives birth to the monstrous serpent Orc. Orc, within Blake’s mythology, is the spirit of revolution, and makes his most substantial appearance in America a Prophecy, the first of Blake’s three “continental prophecies,” in which Blake reworks the recent political history of the world into another iteration of his mythology. As its title suggests, America a Prophecy reworks the recent history of America, specifically the American revolution. It is manifestly not a straightforward retelling of history, not least because of the presence of various gods and monsters. And yet nevertheless the major figures of the American revolution are present within the poem. It opens, for instance, by talking about how “The Guardian Prince of Albion burns in his nightly tent, / Sullen fires across the Atlantic glow to America’s shore: / Piercing the souls of warlike men, who rise in silent night, / Washington, Franklin, Paine & Warren, Gates, Hancock & Green; / Meet on the coast glowing with blood from Albions fiery Prince.”

|

| Figure 415: Urizen, who perverted fiery joy to ten commands, a stony law that Orc stamped to dust. (America a Prophecy Copy A, Object 10, written 1793, printed 1795) |

Appearing to this gathering of American political figures is Orc, who is accused by Albion’s angel of being a “Blasphemous Demon, Antichrist, hater of Dignities; / Lover of wild rebellion. and transgresser of Gods Law.” Orc, for his part, proclaims that “the fiery joy, that Urizen perverted to ten commands, / What night he led the starry hosts thro’ the wide wilderness; That stony law I stamp to dust: and scatter religions abroad / To the four winds as a torn book, & none shall gather the leaves; But they shall rot on desart sands, & consume in bottomless deeps, / To make the desarts blossom, & the deeps shrink to their fountains, / And to renew the fiery joy, and burst the stony roof.” In place of Urizen’s law, then, Orc offers the belief that “every thing that lives is holy, life delights in life; / Because the soul of sweet delight can never be defil’d.” Albion calls upon the colonies to rise up against Orc, but “Silent the Colonies remain and refuse the loud alarm,” and instead they declare independence, with Boston’s Angel asking, “What God is he, writes laws of peace, & clothes him in a tempest / What pitying Angel lusts for tears, and fans himself with sighs / What crawling villain preaches abstinence & wraps himself / In fat of lambs? no more I follow, no more obedience pay.”

|

| Figure 416: Orc's revolution goes rotten as plagues creep on the burning winds driven by his flames. (America a Prophecy Copy A, Object 17, written 1793, printed 1795) |

|

| FIgure 417: The simian fear monster inspired by Goya. (Written by Alan Moore, art by Steve Bissette and John Totleben, From Saga of the Swamp Thing #25, 1984) |

The third monster, after the Monkey King and Swamp Thing, was another suggestion/request on the part of Bissette and Totleben, who were eager to draw a character named Etrigan, created by Jack Kirby during his brief period working for DC. This period followed his falling out with Marvel in 1970 over the fact that Stan Lee continued to get more and more public attention and credit. In late 1969, Kirby had attempted to negotiate an ongoing contract with Marvel, frustrated that for all his contributions to the company he was still being paid as a freelancer, that he didn’t get sufficient creative control over his work (most particularly the Silver Surfer, which he had created entirely on his own, only to have Stan Lee effectively take over the character), and over a series of broken promises by the ever-changing Marvel management, most notably a promise to match whatever settlement was reached with Joe Simon over copyright to Captain America in exchange for Kirby testifying in Marvel’s favor in Simon’s lawsuit. When the contract offer arrived, Kirby found it derisory, and proceeded to sign a contract with DC Comics to begin producing work with them.

|

| Figure 418: For all that DC boasted of having Kirby's talents, they insisted on having his Superman redrawn, as his take was considered too radical. |

|

| Figure 419: Jason Blood transforms into Etrigan for the first time. (By Jack Kirby, from The Demon #1, 1972) |

Moore, Bissette, and Totleben were hardly the first people to draw from Jack Kirby’s store of creations in the years after Kirby’s departure from DC, but it is nevertheless hard not to see the decision to use one of Kirby’s creations, and, perhaps more to the point, to proclaim at the end of the arc that “this story is dedicated with awe and affection to Jack Kirby” as an act of staking out an ideological position. Kirby was always one of the most inventive and original creators in comics, and his work had an odd and visionary quality, especially in the Fourth World saga, which is perhaps the greatest instance of someone creating a new mythology wholesale since William Blake. Essentially everyone in comics recognizes Kirby as one of the greats, but there’s a marvelous ambition on Moore’s part in so quickly identifying his Swamp Thing run as a sort of spiritual cousin to Kirby’s work. (Kirby, for his part, praised Moore’s iconoclasm when they shared a panel with Frank Miller at the 1985 San Diego Comic-Con.)

But the parallels go deeper than Moore could possibly have known in 1984. The frustrations that characterized Kirby’s career, from his feeling that he wasn’t adequately compensated given the amount he’d done for Marvel to his frustrations at lack of creative control at DC, are merely some of the most infamous moments in a long history of labor exploitation in the American comics industry. These issues were ones that Moore and his collaborators were passionate about, and the arc of Kirby’s career at DC, from early days being feted as a visionary genius to eventually leaving in disgust and frustration over DC’s restrictive editorial policies, bears visible parallels to the arc of Moore’s career, right down to their five-year durations.

|

| Figure 420: Etrigan leaps into action. (Written by Alan Moore, art by Steve Bissette and John Totleben, from Saga of the Swamp Thing #26, 1984) |