This is the ninth of twenty-two parts of Chapter Eight of The Last War in Albion, focusing on Alan Moore's run on Swamp Thing. An omnibus of all twenty-two parts can be purchased at Smashwords. If you purchased serialization via the Kickstarter, check your Kickstarter messages for a free download code.

The stories discussed in this chapter are currently available in six volumes. The first volume is available in the US here, and the UK here. The second is available in the US here and the UK here. Finding volume 3-6 are, for now, left as an exercise for the reader, although I will update these links as the narrative gets to those issues.

Moore, when writing the character, tended to imply that he had some Biblical origin, and indeed in 1987 wrote one of four possible origin stories for the character in Secret Origins #10, alongside Dan Mishkin, Paul Levitz, and Mike Barr. Moore’s story is structured as two parallel stories, told on alternating pages, that cover essentially the same ground on different scales. The first is the story of a member of New York’s red-beret wearing Subway Angels, a volunteer organization founded in 1979 to patrol the increasingly dangerous New York Subway, while the second is a set around the fall of Lucifer. In both, the protagonist is torn between two rival factions, fails to commit to either, and is brutally rejected by both as a result. The stories converge in the final two pages as the Phantom Stranger appears to him after he has been beaten and helps him up, giving a solemn speech about how, “lonely inside our separate skins, we cannot know each other’s pain and must bear our own in solitude. For my part,” he explains, “I have found that walking sooths it; and that, given luck, we find one to walk beside us… at least for a little way.”

Finally, Moore introduces the Spectre, a Golden Age hero who served as God’s vengeance, best known for a run of ten issues in the mid-70s written by Joe Orlando and Michael Fleisher, with art by Jim Aparo, which vented Orlando’s frustrations and anxieties after being mugged, with the Spectre meting out gruesome punishments to criminals that skirted the edge of what was permissible under the Comic Code of the time. It is not that any of these characters are particularly obscure, although none had been in particularly active use prior to “Down Among the Dead Men,” with the Phantom Stranger, who had previously had a backing feature in Saga of the Swamp Thing during Pasko’s run, being the closest thing to a regularly appearing character. What the characters were, however, were ones who (along with Swamp Thing himself) would have featured in the comics of Moore’s childhood and adolescence. All of the characters had prominent runs in the late 60s/early 70s that Moore would have been the perfect age for, and that stood out distinctively in the era. They are certainly not the only characters Moore loved, but they nevertheless have ties to a common moment that Moore was both celebrating and updating for the present day. Which was in many ways the point of the exercise. “Down Among the Dead Men” is in no way a complete collection of DC’s mystical and supernatural characters, but it is a thorough enough one, and Moore, by lashing them together into a single story, makes a tacit demonstration that his by now clearly successful approach to writing Swamp Thing was not some fluke, but rather a viable approach to a particular sort of comic in general. And it is telling that “Down Among the Dead Men” roughly coincided with the point where Moore began to get other work at DC.

Pogo was a newspaper strip written and drawn by Walt Kelly, featuring the characters of Pogo the Possum and Albert the Alligator, initially created in 1941 for Dell Comics’ Animal Comics, but made more famous as an editorial page comic in the New York Star and, starting in 1949, as a nationally syndicated comic. The strip is in the grand tradition of American “funny animal” comics and cartoons that accompanied and, gradually, replaced minstrelsy’s role in American comedy. Pogo is an everyman sort of possum living in the Okefenokee Swamp on the Georgia/Florida border along with a menagerie of absurd friends and companions, of which Albert is the most prominent. The comic’s strengths are severalfold. For one, Kelly is a gifted cartoonist whose figures are reliably both expressive and ridiculous. For another, Kelly’s command of language was exquisite in a way few, if any of his contemporaries (or indeed imitators) could match. His characters speak in an invented vernacular long on misspellings and malapropisms, proclaiming things like, “us must git our e-quipments quipped up afore the expedition pedooshes,” and an annual tradition of fractured Christmas carols, the most famous of which began, “Deck us all with Boston Charlie / Walla Walla, Wash., an’ Kalamazoo! / Nora’s freezing on the trolly / Swaller dollar cauliflower alley-garoo!”

Kelly turned these strengths to effective satire, skewering the establishment of American politics in most every direction, most famously in his character “Simple J. Malarkey,” a caricature of anti-Communist crusader Senator Joseph McCarthy. When, in a typically Kellyesque series of events, The Providence Bulletin declared that it would drop the strip if Malarkey appeared again, Kelly responded by simply having the character appear with a paper bag over his head. This was only the most famous of many times Kelly found himself in trouble with the papers distributing his strip, and eventually he settled on the tactic of creating a second set of strips whenever he was doing something controversial. These strips would feature many of the same political points, but in a toned down and subtler manner often featuring cute rabbits as the characters. Kelly, for his part, was open about the practice, making it clear that if readers saw Pogo strips featuring cute bunnies then their newspapers were engaging in censorship.

But for all that Pogo was overtly and satirically political, it was also appreciably broad in its targets. Kelly liked to claim that he was opposed to “the extreme Right, the extreme Left, and the extreme Middle,” and Kelly’s satire, even when it took aim at specific figures, tended to mainly suggest that everyone was in the same absurd and slowly sinking ship, and that the problem with the world was the people in it. This is best exemplified by the most famous quote to come out of the comic, the punchline to a poster Kelly, a committed environmentalist, created for one of the earliest celebrations of Earth Day. The strip features Pogo and another character walking across the swamp, then pulls back to show the mass of litter and junk that they’ve been walking across, as Pogo glumly comments that “we have met the enemy, and he is us.”

Moore’s Pogo homage, fittingly, returns to the ecological themes that characterized his earliest issues of Swamp Thing, and that would come to characterize his best work on the title. The story features a ship of aliens drawn by McManus in a cartoonish and Kelly-esque style, and given a wordplay heavy way of speaking that similarly evokes Kelly’s work. “Don’t be unmembered to tell the Tadling see if old Strigiforme is fetchable nowabouts,” Pog, the leader of the aliens says at one point, before breaking off to marvel at the swamp in which they have landed, saying, “A new Lady! A new Lady as envirginomental as the old one!” Eventually the aliens encounter Swamp Thing (who, in this issue, speaks only in an incomprehensible string of symbols), and explain to him their origin, telling him how on their planet (which they call the Lady) “there was one solitribal breed of misanthropomorphs who refused to convivicate with elsefolk. They constructed their own uncivilization, and exclucified anykind else from joining it. They were the loneliest animals of all. They took our lady away from us.” He goes on to explain the horrible things these animals did, running medical experiments and, worse, killing and eating the other creatures until Pog and his shipmates set forth in their ship Find-the-Lady to find a new Lady on which to live, which Pog believes that they have now done.

The stories discussed in this chapter are currently available in six volumes. The first volume is available in the US here, and the UK here. The second is available in the US here and the UK here. Finding volume 3-6 are, for now, left as an exercise for the reader, although I will update these links as the narrative gets to those issues.

Previously in The Last War in Albion: Alan Moore's third arc on Swamp Thing featured a tremendously disturbing scene in which it is revealed that Abby has been being raped by her dead uncle who has taken over her husband's body. The scene failed to pass muster with the Comic Code Authority, the industry's self-appointed censor, leading DC to take the momentous decision to simply publish Swamp Thing without Code approval.

"With each terrible death and resurrection, Crafty knew that by his torment, the world was redeemed. It seemed there was nothing that could truly kill him, and while he lived there still remained the hope that one day he might return and on that day overthrow the tyrant God and build a better world."- Grant Morrison, Animal Man #5

|

| Figure 435: Swamp Thing and Arcane meet again in hell. (Written by Alan Moore, art by Steve Bissette and John Totleben, from Swamp Thing Annual #2, 1984) |

After its initial splash of controversy the Arcane trilogy resolved more or less predictably, albeit with the substantial wrinkle of Arcane killing Abby. Ultimately Matt Cable wrests control of his body back and casts Arcane back down to hell before using the last of his lingering superpowers to bring Abby back from the dead. Unfortunately, Matt is only able to revive her body, leaving Swamp Thing to journey into the afterlife to rescue her soul from hell, where Arcane cast it down. This journey is depicted in Swamp Thing Annual #2, a forty-page saga called “Down Among the Dead Men.” Moore has described the story as an attempt to provide “a preliminary map - a rough map - of the DC supernatural territories,” which is as good a description as any for a spiritual journey into the DC Universe versions of heaven and hell. Structurally speaking, the story is intensely episodic - Swamp Thing allows his consciousness to sink into the Earth, and then further into the realms of death. There he proceeds to meet a series of minor supernatural characters from DC history alongside a series of short encounters with various entities in the realms he explores. The two most notable of these are a scene where he meets Alec Holland in heaven, finally getting to exchange words with the man he thought he was, and a scene in which he meets Arcane, who is being tortured by vast numbers of insect eggs hatching inside his body. As Swamp Thing walks on, Arcane begs him, “huh-how many years have I buh-been here?” and Swamp Thing turns, a beautifully cruel smile on his face, and answers simply, “since yesterday.”

|

| Figure 436: A characteristically dynamic page layout from Neal Adams's early career work on Deadman. (Written by Carmine Infantino and Jack Miller, from Strange Adventures #207, 1967) |

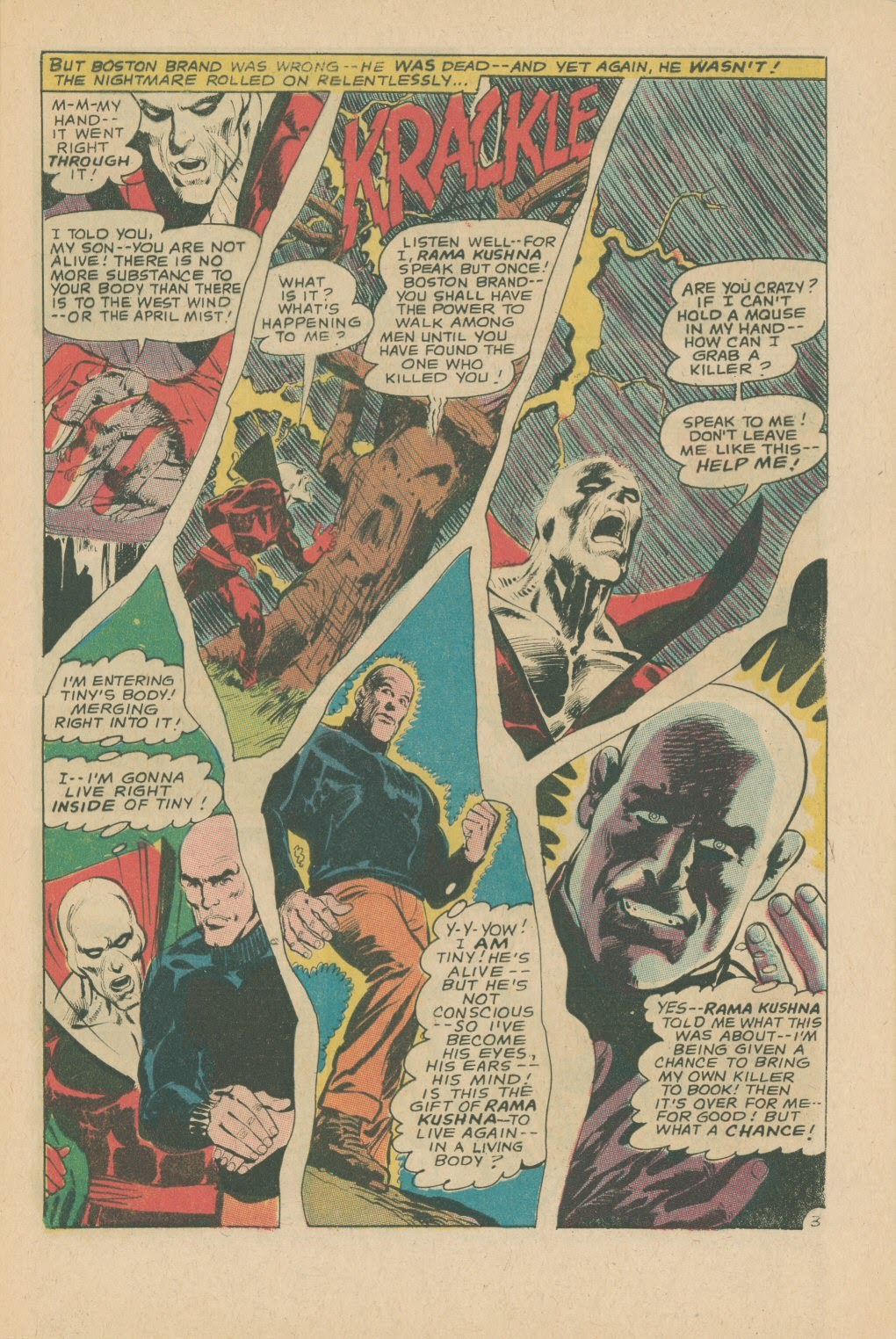

These short scenes pack a reasonable emotional punch, but in many ways it is the larger canvas that is interesting in “Down Among the Dead Men,” and particularly the set of characters Moore selects to serve as Swamp Thing’s guides, which included a return of Etrigan alongside three other characters from DC’s long history. First among them is Deadman, a character created in the late 1960s by Arnold Drake and Carmine Infantino for Strange Adventures, a long-running title that, over the years, wandered around through many premises and presentations but was, in the late sixties, a supernatural fantasy book. Deadman was the circus name of Boston Brand, a trapeze artist murdered during a performance, but who was allowed to remain as a ghost who could possess the bodies of people by a goddess named Rama Kushna (a bastardization of the real gods Rama and Krishna) so he could hunt his killer. In many ways Deadman is most notable for providing the first ongoing work for Neal Adams, who would go on to become the iconic comics artist of the 1970s for his dramatic page compositions, often featuring pages of angled, non-rectangular panels drawn from low-to-the-ground perspectives that, combined with a style honed by years working on photorealistic drama strips syndicated to newspapers, gave his characters a staggering, larger than life presence. Deadman himself is a ridiculous character, not least due to his appearance as a gaunt, white corpse in a circus outfit, who suffered from the same problem Moore identified in Swamp Thing whereby the seeming premise of the series (in this case Deadman’s quest to find his killer) could never be resolved or else

the series would end (since Deadman’s unlife explicitly lasts until he finds his murderer). But as with the

original run of Wein/Wrightson Swamp Thing tales, there is much to like in the original run of stories.

the series would end (since Deadman’s unlife explicitly lasts until he finds his murderer). But as with the

|

| Figure 437: The first appearance of the Phantom Stranger. |

The second character Moore dusts off is a rather stranger one: John Broome and Carmine Infantino’s The Phantom Stranger, who first appeared in a six-issue series bearing his name in 1952, where he appeared in a variety of short stories all of which had basically the same plot. Initially some apparently supernatural event would occur, bringing misfortune to people. At a moment of crisis, the Phantom Stranger appears out of nowhere, resolves the situation, generally revealing it to have a mundane explanation. After a sixteen year gap, he appeared again in an issue of Showcase, then got a second series in which he was reworked as an actually supernatural character. Through all of this, the Stranger pointedly never received anything like an origin story or explanation of where he came from, a conceit that gave him a certain appeal.

|

| Figure 438: In one four possible origin stories, the angel that became the Phantom Stranger has his wings torn off. (Written by Alan Moore, art by Joe Orlando, from Secret Origins #10, 1986) |

|

| Figure 439: The staggering scale of the Spectre is revealed to Swamp Thing and the Phantom Stranger (Written by Alan Moore, art by Steve Bissette and John Totleben, from Swamp Thing Annual #2, 1984) |

With “Down Among the Dead Men” both being an oversized story and one published as an Annual, meaning that it came out the same month as Swamp Thing #32, another fill-in issue was needed to keep the book on schedule. Having given Shawn McManus a rather frustratingly ill-suited story in “The Burial,” Moore was eager to give him something more immediately suited to his cartoonish style, and so penned a bespoke story called “Pog” that serves as one of the oddest installments of Moore’s run. As Moore explains it, the idea came to him while he was brainstorming “characters that live in swamps - and I just put Pogo.”

|

| Figure 440: Although best known as a newspaper strip, Pogo made his first appearance in Dell's Animal Comics #1. |

|

| Figure 441: Simple J Malarkey, a parody of Joseph McCarthy, in a 1953 Pogo strip by Walt Kelly. |

|

| Figure 442: Arguably the most famous Pogo strip was Kelly's poster for the 1971 Earth Day. |

|

| Figure 443: Pog explains his history to Swamp Thing by drawing pictures on the ground. (Written by Alan Moore, art by Shawn McManus, from Swamp Thing #32, 1984) |

In response, Swamp Thing sadly takes Pog to Baton Rouge to show him the nature of the planet on which they have landed - a silent sequence of humans cooking and eating meat, which Pog stares at in dumbstruck horror before weeping and crying out that “they can’t own this Lady too! We were going to be happy here!” [continued]