This is the eighteenth of twenty-two parts of Chapter Eight of The Last War in Albion, focusing on Alan Moore's run on Swamp Thing. An omnibus of all twenty-two parts can be purchased at Smashwords. If you purchased serialization via the Kickstarter, check your Kickstarter messages for a free download code.

The stories discussed in this chapter are currently available in six volumes. This entry covers stories from the fourth volume. It's available in the US here and UK here. Finding the other volumes are, for now, left as an exercise for the reader, although I will update these links as the narrative gets to those issues.

The stories discussed in this chapter are currently available in six volumes. This entry covers stories from the fourth volume. It's available in the US here and UK here. Finding the other volumes are, for now, left as an exercise for the reader, although I will update these links as the narrative gets to those issues.

Previously in The Last War in Albion: Alan Moore paid off a year of eschatological foreshadowing with the unleashing of the primordial spirit of evil itself in a bizarre South American death ritual conducted by the Brujería, who represent the blackness at the heart of America.

"We all woke up, the day after the world ended, and we still had to feed ourselves and keep a roof over our heads. Life goes on, y'know?" - Alan Moore, Promethea

|

| Figure 508: Judith's transformation is a triumph of psychedelic body horror. (Written by Alan Moore, art by John Totleben, from Swamp Thing #48, 1986) |

The unleashing of this horror, in “A Murder of Crows,” in Swamp Thing #48, comes when one of Constantine’s allies, Judith, betrays him to the Brujería and agrees to serve as their messenger. This involves a ritual in which Judith vomits out her intestines and allows her body to shrivel until only her severed but still talking head remains. The Brujería then place a black pearl in her mouth, at which point her head steadily transforms into a bird, a process that is laboriously and disturbingly described, at which point the bird is released to summon the nameless dark power by delivering a pearl held in its mouth to a distant destination. Although this transformation is presented as a physical corruption ripe with body horror, the fact that it is brought about via Judith ingesting an unnamed root places it in the larger thematic tradition of psychedelic plants within Moore’s Swamp Thing. It is, in other words, inexorably linked with the bad trip - the negative, monstrous aspect of the spiritual plane.

|

| Figure 509: Swamp Thing meets his ancestors in the Parliament of Trees. (Written by Alan Moore, art by Stan Woch and Ron Randall, from Swamp Thing #47, 1986) |

But the summoning of this dark power is the third issue of the arc. The second, coming between it and the Crisis tie-in, presents a second, equally important aspect of this setup. In it, before journeying to the Brujería’s cave, Constantine takes Swamp Thing to the Parliament of Trees, also located in South America, in this case at the source of the River Tefé in the Amazon. Here Moore pays off the idea introduced in “Abandoned Houses,” revealing the resting place of all the past plant elementals of the world and allowing Swamp Thing to seek communion with them. In yet another sequence of psychedelia, Swamp Thing allows his mind to meld with that of the parliament, where he asks the “eternal trees” about the coming apocalypse, asking “how to use my power to its best advantage.” The Parliament recoils, saying, “power? Power is not the thing. To be calm within oneself, that is the way of the wood.” When Swamp Thing expresses doubt, saying that he has “seen much that is evil… it preys upon my mind. I wonder if nature can be just to allow such things,” the Parliament further rebukes him, telling him that “flesh doubts. Wood knows. If you wish to understand evil, you must understandt he bark, the roots, the worms of the earth. That is the wisdom of an Erl-King. Aphid eats leaf. Ladybug eats aphid. Soil absorbs dead ladybug. Plant feeds upon soil. Is aphid evil? Is ladybug evil? Is soil evil? Where is the evil in all the wood?” And with that, Swamp Thing is cast out of the Parliament, much to his horror.

Taken together, these issues mirror the basic structure of “Windfall,” with “The Parliament of Trees” serving as Sandy’s half of the story and “A Murder of Crows” serving as Milo’s. These two aspects of the spiritual experience are, at least superficially, being pitted against each other, and yet in the Parliament’s answer there is already the setup for this debate’s inevitable resolution. This resolution occupies the final two issues of the arc, including the oversized Swamp Thing #50.

|

| Figure 510: Marv Wolfman became the second writer to tackle John Constantine. (Art by George Perez and Mike DeCarlo, from Crisis on Infinite Earths #4, 1985. Composite of two pages.) |

These issues, perhaps surprisingly, return the focus to the larger DC Universe. With the Brujería’s messenger released, Constantine is forced to drop to plan B - preparing to battle the entity they’ve summoned once it arrives. This involves Constantine and Swamp Thing parting ways again to handle parallel tasks. Constantine, for his part, begins meeting with various mystical figures within the DC Universe: Marv Wolfman and Gene Colan’s Baron Winters, John B. Wentworth and Howard Purcell’s Golden Age creation Sargon the Sorcerer, a character created for Action Comics #1 by Fred Guardineer called Zatara, along with his Gardner Fox/Murphey Anderson-created daughter (and Justice League member) Zatanna, the pre-Superman Siegel and Shuster creation Doctor Occult (who shows up uninvited), and finally Arnold Drake and Bruno Premiani’s Steve Dayton, “the world’s fifth richest man,” who created a helmet to increase his mental powers and who goes by the name of Mento. This latter character’s inclusion was foreshadowed back in Crisis on Infinite Earths #4, where Constantine meets with him in a more or less contextless eight-panel scene wedged between a scene with Batgirl and Supergirl and one in which Pariah, a character created for Crisis, witnessing more earths dying (which is most of what he does in the story), an appearance that was followed up on by an equally cryptic sequence in Swamp Thing #44 (“Bogeymen”). Swamp Thing, on the other hand, connects back with the various characters he met back in “Down Among the Dead Men” in order to confront the being on the spiritual plane.

|

| Figure 511: Zatara bursts into flames, his top hat sickly and hilariously unaffected. (Written by Alan Moore, art by Steve Bissette, Rick Veitch, and John Totleben, from Swamp Thing #50, 1986) |

The oversized Swamp Thing #50, which also served as Steve Bissette’s final issue as the book’s primary penciller, finally offers this confrontation, with a series of supernatural beings attempting to defeat the summoned being and failing before Swamp Thing finally saves the day. While this is going on, Constantine and his allies watch via Mento’s psychic powers, narrating events and, as Constantine explains it, channeling their magical energies to help Swamp Thing and his allies, which results in the incineration of both Sargon and Zatara due to psychic backlash from the blackness. The confrontation itself consists of four characters fighting their way to the gigantic shadow at that is the nameless entity, where they are grabbed and forcibly drawn into it to confront it.

|

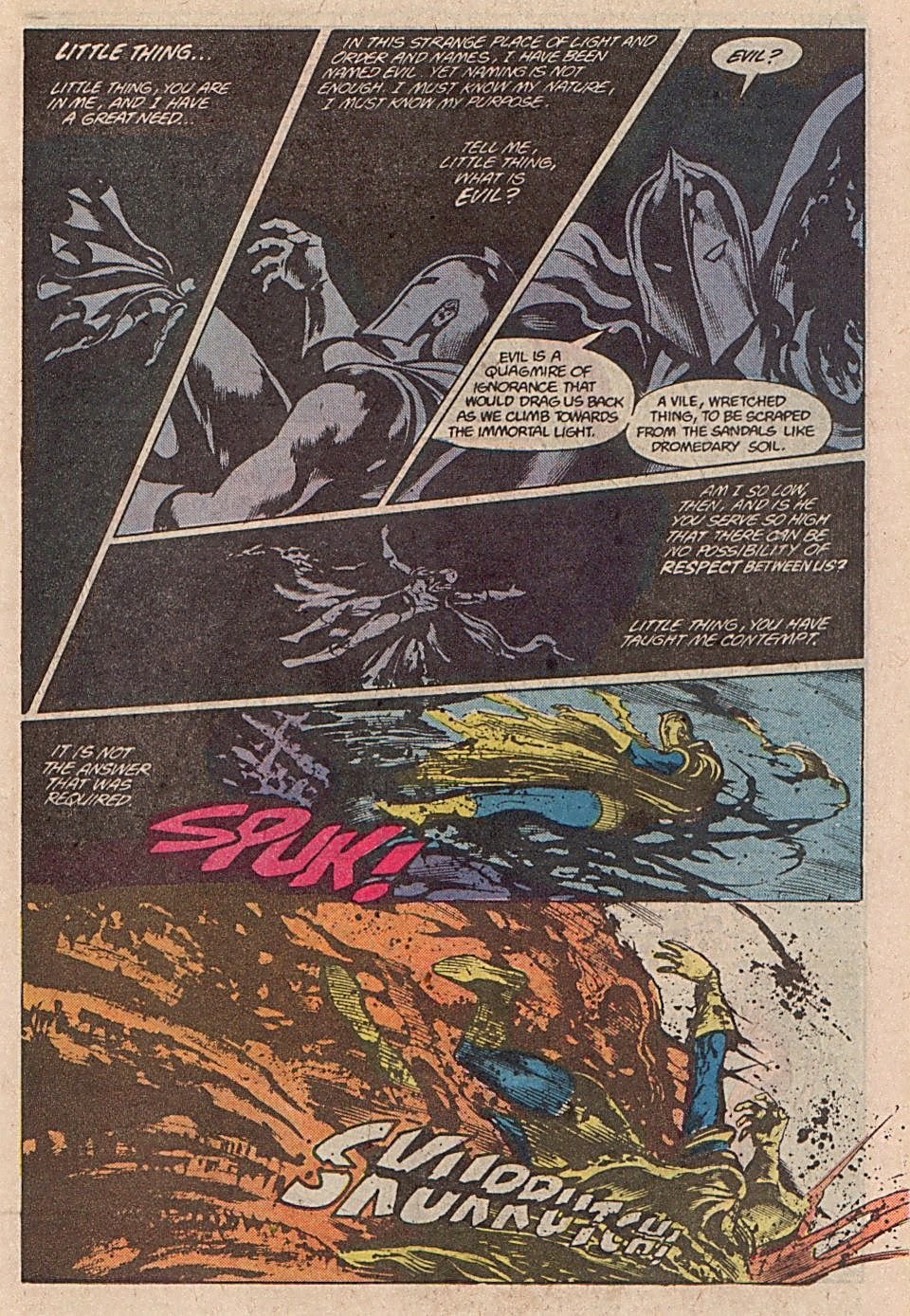

| Figure 512: Doctor Fate fails to appease the horrible darkness. (Written by Alan Moore, art by Steve Bissette, Rick Veitch, and John Totleben, from Swamp Thing #50, 1986) |

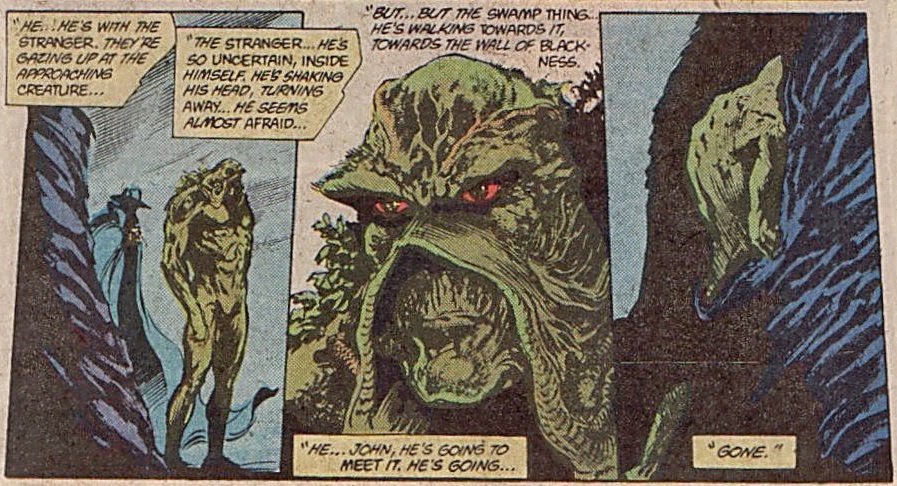

These confrontations are depicted as sequences in which the characters float in an immense blackness, which addresses them in turn, asking each a question. They in turn answer and, as the shadow finds their answers unacceptable, are cast out. First is Etrigan, to whom the shadow explains, “before light, I was; enldess, without name or need of name. Then light came. Witnessing its otherness, I suffered my first knowledge of self, and all contentment fled. Tell me, little thing. Tell me what I am.” Etrigan, for his part, explains that the darkness is “evil, absence of god’s light, his shadow-partner, locked in endless fight.” But the shadow is unimpressed, claiming all Etrigan has taught it is fatalism and inevitability, and that these are not what it needs. Next is Doctor Fate, a Golden Age magical character, who, when asked, “Little Thing, what is evil,” replies that “evil is a quagmire of ignorance that would drag us back as we climb towards the immortal light. A vile, wretched thing, to be scraped from the sandals like dromedary soil.” Again, the shadow is unimpressed, saying that Doctor Fate has only taught it contempt and casting him out. At last comes the Spectre, who, asked the same question as Doctor Fate, proclaims that “evil exists only to be avenged, so that others may see what ruin comes of opposing that great voice, and cleave more wholly to its will, fearing its retribution,” to which the shadow says that the Spectre has taught it only vengeance and casts him out. At this point it appears that all hope is lost, and even the Phantom Stranger seems to give up. But Constantine, for his part, demands to know what Swamp Thing is doing, shouting that “this is what I prepared him for!” Swamp Thing, for his part, walks willingly into the blackness.

|

| Figure 513: Swamp Thing willingly enters the darkness to confront the hideous beast. (Written by Alan Moore, art by Steve Bissette, Rick Veitch, and John Totleben, from Swamp Thing #50, 1986) |

Here, then, Moore sets the stage for his larger philosophical confrontation. Having identified a fundamental rot within this new continent in which his tales are to be unleashed, he has now brought an apocalyptic force to devour it. More than that, he has lent this final judgment a moral rightness. To Doctor Fate’s contempt, it quite reasonably asks, “am I so low, then, and is he you serve so high that there can be no possibility of respect between us?” And to the Spectre’s suggestion that evil exists only to be punished, it asks, “what of the tortured eons I endured, unable to broach this maddening brilliance and quiet the pain it woke in me? Do they not demand retribution?” In this final question, the darkness brings up a fundamental and previously unspoken aspect of Moore’s story. The darkness is, by this point, being portrayed as the nothing in which God created light, an event that has tortured it with knowledge of self ever since. This has parallels in the basic idea of an American darkness and of the Brujería. The depiction of them as existing in the furthest reach of the continent raises the question of what exists in the rest of the continent. The answer, of course, is the product of European colonialism, which led to the overthrow and oppression of the indigenous population to which the Brujería belong. This colonialism is mirrored in the darkness’s pain at being invaded by light, and the angry vengeance that it comes to demand serves as a metaphor for the oppressed and subaltern indigenous populations. The darkness is not evil, in this analogy, but rather a righteous demand for justice on the part of the deeply aggrieved, with the European light being the true villain of the piece.

|

| Figure 514: Swamp Thing discusses the nature of evil with its embodiment. (Written by Alan Moore, art by Steve Bissette, Rick Veitch, and John Totleben, from Swamp Thing #50, 1986) |

And yet having engineered this conflict carefully over the course of more than a year of comics, at the final moment Moore opts to avert it. Swamp Thing, when faced with the darkness’s question about the nature of evil, at first reflects on the evil he witnessed during the “American Gothic” arc: “its cruelty… the randomness with which it ravages… innocent… and guilty alike.” But then he comes to the council given by the Parliament of Trees, admitting that he did not understand their answer. “And yet,” he says, “they spoke of aphids eating leaves, bugs eating aphids, themselves finally devoured by the soil, feeding the foliage. They asked where evil dwelled within this cycle and told me to look to the soil. The black soil is rich in foul decay… yet glorious life springs from it. But however dazzling the flourishes of life, in the end, all decays to the same black humus… Perhaps evil,” he finally concludes “is the humus formed by virtue’s decay… and perhaps… perhaps it is from that dark, sinister loam that virtue grows strongest?” This answer, at last, is satisfactory to the darkness, which allows Swamp Thing to leave freely while it reflects upon what he has said, and then finally confronts the light, depicted as a double page spread of two massive hands reaching towards each other. The scene is narrated by Dayton, who is driven hopelessly mad by the experience and left unable to describe it. Instead Moore offers only the cryptic words of the Phantom Stranger, who says that “the light and shade are still everywhere around us… only the conflict between them has altered,” later musing that “in the heart of darkness, a flower blossoms, etching the shadows with its promise of hope… in the fields of light, an adder coils, and the radiant tranquility is lent savor by its sinister presence. Right and wrong, black and white, good and evil… all my existence I have looked from one to the other, fully embracing neither one… never before have I understood how much they depend upon each other.”

|

| Figure 515: (Art by Eddie Campbell, from Snakes and Ladders, 2001) |

Within this ending there is a kernel of interesting observation that Moore, in his usual obliquely unchanging manner, would return to in his later career when, for example, he had Promethea muse that “if Qlippoths are husks left when good departs, does that mean evil isn’t a real thing, in itself? It’s just an absence of good, like dark’s an absence of light?”, or when, in Snakes and Ladders, he writes that “the profane and sacred are both one, and that the salt of the earth and its scum are struck from the same coin, and in our lowest depths, the worst abyss of us, there is a light.” There are, to be sure, profound implications to this sort of thing - it’s an insight not unlike that of Blake when he wrote that “Without Contraries is no progression. Attraction and Repulsion, Reason and Energy, Love and Hate, are necessary to Human existence. From these contraries spring what the religious call Good & Evil. Good is the passive that obeys Reason, Evil is the active springing from energy. Good is Heaven. Evil is Hell” in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell.

|

| Figure 516: The inscrutable resolution to Alan Moore's first apocalypse. (Written by Alan Moore, art by Steve Bissette, Rick Veitch, and John Totleben, from Swamp Thing #50, 1986) |

And yet for all of this, there is something frustratingly hollow about the resolution. There is no describable change effected by Moore’s resolution. Good and evil are said to have the same relationship as ever, although the Phantom Stranger concedes that perhaps “a different light has been cast upon their relationship.” But within the confines of DC’s superhero line, in which the comic is tacitly grounded, this seems set to mean little. A “no-score draw,” as Constantine describes the outcome, inherently favors the side that had power at the outset - that is, the light that has banished the darkness to a point depicted as “a chaotic inferno with neither land nor sky” beyond the edges of reality itself. DC Comics and its multitude of superhero franchises will continue to embrace “good,” and by extension to embrace the status quo. The light will always retain its tacit allegiance with entrenched power structures, and the darkness will never have its vengeance for the light’s invasion of it.

|

| Figure 517: The Peacemaker, whose death was to be made into a mystery by Alan Moore. |

The fundamentally conservative nature of this ending is stressed by the issue’s final page, which returns to Cain and Abel. Abel reflects upon the situation, noting that “nearly all our stories revolve around good struggling against evil… darkness against light… what will become of the stories? Without that ancient conflict to fall back on, what will they be about?” Cain’s answer, of course, is to shove his brother off a cliff to his death with a wisecrack about how he’s “sure we’ll think of something,” a moment that reiterates the complete lack of change offered by this resolution. This is not, as Moore would later write in Promethea, a conceptual apocalypse with the real possibility of transforming the world. Rather, it’s a damp squib - a whimpering end of the world wholly devoid of bang.

It is not fair, however, to frame this as a failing on Moore’s part. For all that he was rapidly becoming the golden boy of DC Comics, Moore was never going to be allowed to fundamentally and irrevocably alter the nature of the DC Universe, and he was certainly not naive enough to think otherwise. He had, after all, by this point, already had his plans for a story called Who Killed the Peacemaker? [continued]