Comics Reviews will return on February 11th.

This is the ninth of fifteen parts of The Last War in Albion Chapter Nine, focusing on Alan Moore's work on V for Vendetta for Warrior (in effect, Books One and Two of the DC Comics collection). An omnibus of all fifteen parts can be purchased at Smashwords. If you purchased serialization via the Kickstarter, check your Kickstarter messages for a free download code.

The stories discussed in this chapter are currently available in a collected edition, along with the eventual completion of the story. UK-based readers can buy it here.

This is the ninth of fifteen parts of The Last War in Albion Chapter Nine, focusing on Alan Moore's work on V for Vendetta for Warrior (in effect, Books One and Two of the DC Comics collection). An omnibus of all fifteen parts can be purchased at Smashwords. If you purchased serialization via the Kickstarter, check your Kickstarter messages for a free download code.

The stories discussed in this chapter are currently available in a collected edition, along with the eventual completion of the story. UK-based readers can buy it here.

Previously in The Last War in Albion: Guy Fawkes tried to blow up the Houses of Parliament.

"Earth 43: A world of darkness and fear where super-vampires rule the night as the BLOOD LEAGUE." -Grant Morrison, Multiversity Guidebook

|

| Figure 621: William of Orange was crowned William III in the Glorious Revolution. Here his 1688 arrival is depicted by James Thornhill (1675-1734). |

It is not that this is entirely unsympathetic. Fawkes himself was a Catholic supremacist, but he fit into the same centuries-long tradition of religious dissidence in England that would eventually produce William Blake. And as David Lloyd noted, the basic cheek of trying to blow up Parliament is rather appealing. In the end, though, is not so much the precise ethics of Fawkes the man that are most relevant to the development of V for Vendetta as it is the holiday that sprung up in the wake of the plot. Following its uncovering, the public were allowed to celebrate the plot’s failure by lighting bonfires. The next January, Parliament passed the Observance of 5th November Act, which established a standing holiday commemorating the King’s survival. This holiday persisted, not least because in 1688 William of Orange’s arrival in England to overthrow James II happened to land on November the 5th, the day after his birthday, giving the holiday new resonances. Over time the custom of bonfires came to incorporate first burning the pope in effigy, and then, somewhat more moderately, burning Guy Fawkes in effigy - a tradition that led to the creation of the Guy Fawkes mask, with allowed one to give one’s anti-Catholic effigy a suitably grotesque holiday.

|

| Figure 622: An 1870s effigy of Guy Fawkes built by a London fruitvendor. |

The holiday also, in the 19th century, gradually became a holiday more associated with the working class, a transition that led to a transition away from celebration of victories of the monarchy and towards a more anti-authoritarian approach. Over the course of the century, Fawkes found himself incorporated into popular fiction, starting with William Harrison Ainsworth’s 1841 novel Guy Fawkes, which rehabilitated Fawkes into a more sympathetic character who, by 1905, was appearing as a hero in illustrated books like The Boyhood Days of Guy Fawkes; Or, the Conspirators of Old London. This was very much the spirit in which Moore was introduced to the holiday - he talks of how “when parents explained to their offspring about Guy Fawkes and his attempt to blow up Parliament, there always seemed to be an undertone of admiration in their voices, or at least there did in Northampton.”

|

| Figure 623: A 1981 anti-Thatcher riot in Toxteth. |

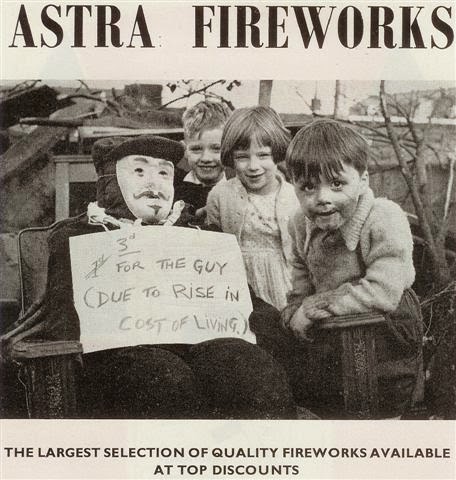

But Moore and Lloyd’s intercession proved well-timed as well. Moore mentions that the autumn of 1981, when they were developing V for Vendetta, was the last year that the mask was widely available before it was “phased out in favour of green plastic Frankenstein monsters geared to the incoming celebration of an American Halloween.” The specific dating of this transition is surely exaggerated by Moore, but it is true that the specific link between the holiday and Guy Fawkes was in decline at the time, with the holiday gradually becoming more known as Bonfire Night. (Moore notes that this was unsurprising following “a summer of anti-Thatcher riots across the UK.”) Moore and Lloyd, then, found themselves in the fortuitous position of having based their comic on an image that was popular enough to be immediately recognizable, but that was also losing its stature such that they could imbue it with meaning relatively unfettered by its material past.

%2B(small).jpg) |

| Figure 624: A 1965 advertisement for fireworks featuring a paper Guy Fawkes mask. |

So what matters about Guy Fawkes is ultimately the way in which a symbol of radical and transgressive rejection of institutional power gradually became a more ambivalent symbol while also shedding most of the particulars of what that rejection actually consisted of, such that he became, in effect, a sort of socially sanctioned symbol of general insurrection. Combined with the image of the Guy Fawkes mask itself, which allowed Moore to render his central character a faceless and expressionless cipher, the idea allowed him a main character who embodied not any specific ideology, but rather a sort of generic objection to all ideologies - an approach summed up by Moore’s decision to title the first chapter of V for Vendetta“The Villain” and to give V his line proclaiming, “I’m the King of the Twentieth Century. I’m the bogeyman. The villain. The Black sheep of the family.” In other words, to the rejection of authority implicit in anarchism.

|

| Figure 625: Dennis the Menace being spanked in 1969. |

But what is striking about V and the Guy Fawkes mask is its connection to an authorized rejection of authority. The 19th century transformation of the fifth of November into a working class holiday fits into a longstanding tradition of carefully controlled rebellion common to the British children’s comics like The Beano and The Dandy. Guy Fawkes Night was, in many ways, a structural mirror of any given installment of Dennis the Menace - both feature a gleeful subversion of the social order with lots of explosions and mayhem, but more importantly, both also promptly end, Dennis the Menace, generally, with the reassertion of authority implicit in Dennis being spanked, Guy Fawkes Night by the rollover of the calendar onto another grim Victorian workday. Guy Fawkes represents a sanctioned rebellion - a specific place that institutional power allows dissent to exist, largely to keep it from existing anywhere else.

.jpg) |

| Figure 626: Max Ernst's Europe after the Rain II (1940-42) |

But as Moore recognized, the fact that rebellion is an assumed part of the social order is itself a source of power. And Guy Fawkes serves as an effective image of this simply because of the sheer degree of rebellion he represents. If an attempt to blow up Parliament and assassinate the king can be recuperated into society as an authorized rebellion, the space available to rebellion is, perhaps, larger than it initially appears. And indeed, this helps explain why Lloyd’s Guy Fawkes suggestion caused the entire concept to click together for Moore. In “Behind the Painted Smile,” Moore recalls a list he made of things he wanted to include or reflect in V for Vendetta. The list he offers in “Behind the Painted Smile” reads: “Orwell. Huxley. Thomas Disch. Judge Dredd. Harlan Ellison’s Repent Harlequin Said the Tick-Tock Man. Catman and Prowler In The City At The Edge Of The World by the same author. Vincent Price’s Dr. Phibes and Theatre of Blood. David Bowie. The Shadow. Night-Raven. Batman. Farenheit 451. The writings of the New Worlds school of science fiction. Max Ernst’s painting ‘Europe After the Rains’. Thomas Pynchon. The atmosphere of British Second World War films. The Prisoner. Robin Hood. Dick Turpin…”

This is, obviously, a somewhat ludicrously diverse list, and that is in many regards the point. Everything upon the list is indeed reflected within V for Vendetta to some extent, and most (though not all) feature some consideration of a singular figure rebelling against an authoritarian regime, to varying degrees of effect, and, perhaps more notably, with various degrees of skepticism about that rebellion. But as Moore explains, “there was some element in all of these that I could use, but try as I might I couldn’t come up with a coherent whole from such disjointed parts.” But after Lloyd’s Guy Fawkes idea was mooted, the connection Moore was looking for finally emerged - the British “tradition of making heroes out of criminals.” In a 2005 interview, Moore went further, highlighting how many of the characters along these lines are “sociopaths” who are “thoroughly unpleasant,” noting that “we love a gallant rogue and we also love a murdering, psychotic, horrific travesty of a human being. I thought that maybe I could exploit this.”

|

| Figure 627: Advertisement for David J's V for Vendetta single and other merchandise. (From Warrior #24, 1984) |

This fascination with the intersection between the marginalized and mainstream elements of culture and with the notion of authorized rebellion also sheds light on one of Moore and Lloyd’s collaborators in V for Vendetta, David J, who wrote the music for “This Vicious Cabaret” and who went on to record an official V for Vendetta EP featuring his own rendition of “This Vicious Cabaret” along with a setting of the cabaret song from “Variety” and some instrumental pieces. David J would go on to be a member of Moore’s magical society The Moon and Serpent Grand Egyptian Theatre of Marvels, contributing to Moore’s five spoken word workings in the 90s and early 00s, and so it is worth pausing to unpack his contributions to Moore’s earlier career, and, for that matter, Moore’s early contribution to David J’s career, which began in earnest, like Moore’s, in 1979 with the formation of the band Bauhaus.

|

| Figure 628: Poster for a 1983 Bauhaus event. |

In many ways, Bauhaus was just a subtle alteration on several previous bands that had formed in Northampton, generally featuring some combination of David J, his younger brother Kevin Haskins, and Daniel Ash. In late 1978, Haskins and Ash formed one with bassist Chris Barber and a friend of Ash’s, Peter Murphy, as the vocalist. (Murphy, despite the fact that he had no musical experience to speak of, in Ash’s opinion, looked right for a lead vocalist.) After a few weeks, however, Ash decided Barber was not really working out, and instead invited David J as bassist. J suggested the band’s name based on his love of the German art school of the same name, originally proposing Bauhaus 1919 (the year of the school’s foundation) before shortening it to simply Bauhaus, and they played their first official gig as a New Year’s Eve show (having previously crashed a Pretenders show by bringing their own amps to the union hall where the band was going to play and simply setting up and starting playing their own set).

Two days later, while biking home from a warehouse job, David J had an idea for a lyric, and stopped to jot it down on the back of a series of address labels. He took it to rehearsal that night, and Ash matched it with a chord structure based around a sliding barre chord that left the E and B strings open. Haskins added a bossa-nova drumbeat (J notes that “he had been taking lessons from an old jazz guy, and this was one of the two beats he knew”), and J opted for a simple walking bassline, over which Murphy sang the lyric: “White on white, translucent black cape’s back on the rack… Bela Lugosi’s dead.” As J describes it, “we all just fell in with each other. It was as if we had been playing this strange song for years.” They debuted it the next day at a gig in Kingsthorpe, and went into the studio to record it and some other tracks a couple of weeks later.

|

| Figure 629: Poster for the 1931 Universal Dracula film, starring Bela Lugosi. |

Given that the song was in effect the product of a jam session, the sweep and scale of the studio version is perhaps not entirely surprising. It is, however, undoubtedly impressive: the song clocks in at nine-and-a-half minutes long. The melody is driven entirely by David J’s baseline for the first ninety seconds of the song, starting with him plucking the first note of his three-note bass line, then beginning the walkdown, letting each of the three notes hang. Only after those first ninety seconds is there any variation, and that just consists of him filling in the extra beats of each measure with repetitions of the note as Ash adds a trilling guitar effect with a hammer-on. The chords don’t make an appearance until 2:20; the vocal line takes until nearly the three minute mark. There’s another ninety seconds of vocal-free ambience at five minutes, and the last two minutes are also almost totally wordless, and, indeed mostly just feature Haskins’s drumming with occasional bass interjections from David J. These long expanses in which the song is left only to its simple and sparse instrumentation, augmented only by some echo effects whipped up by Ash after studio engineer Derek Tompkins taught him how to use a delay unit, the song has an ethereal tone that suits its vampiric subject matter. Equally crucial, however, is Murphy’s voice - a luscious baritone that hits the exact mix of austerity and camp necessary to sell a song about the star of the 1931 Universal Dracula film that includes the lines “The virginal brides file past his tomb, strewn with time’s dead flowers, bereft in deathly bloom” and repeated chants of “undead undead undead.” As Alan Moore put it, “Jay’s bass and Haskins’ drums provided the music with its elegant and powerful metal skeleton, while Murphy’s hard, haunting voice and Ash’s molten glass guitar provided its white, jewel-studded flesh.”

The result was a minor hit that stuck around in the independent charts for two years and, perhaps more significantly, marked the birth of goth music. [continued]