This is the ninth of eleven parts of The Last War in Albion Chapter Ten, focusing on Alan Moore's Bojeffries Saga. An omnibus of all eleven parts is available on Smashwords. If you are a Kickstarter backer or a Patreon backer at $2 or higher per week, instructions on how to get your complimentary copy have been sent to you.

The Bojeffries Saga is available in a collected edition that can be purchased in the US or in the UK.

The Bojeffries Saga is available in a collected edition that can be purchased in the US or in the UK.

Previously in The Last War in Albion: Alan Moore was particularly passionate about his handful of collaborations with Bryan Talbot. But his major effort at collaborating with Talbot, a strip to be called Nightjar and be published in Warrior, was never completed.

"The world must be warned about those ducks. It's all true."-Translucia Baboon, quoted by Neil Gaiman

|

| Figure 776: The opening to Nightjar, unpublished for twenty years. (Written by Alan Moore, art by Bryan Talbot c. 1983, published in Yuggoth Cultures #1, 2003) |

Nightjar ultimately became a casualty of Moore’s falling out with Dez Skinn, who, for his part, insists that he “was never very keen on Nightjar (hated the name) and Bryan was another slow - or busy - artist, so it would never have happened in Warrior.” Talbot ultimately only completed two and a half pages of the strip, with another page partially completed, but roughly twenty years after Talbot had started the page, William Christensen at Avatar got in touch and asked if he still had the unfinished pages. Talbot did, and Christensen proceeded to commission Talbot to finish the strip, reprinting it along with the script and Moore’s letter to Talbot about the development of it in the first issue of the anthology Yuggoth Cultures, collecting various Moore obscurities with newly commissioned adaptations of some of his poems and song lyrics.

|

| Figure 777: The seven villainous sorcerers who killed Mirrigan's father. (Written by Alan Moore c. 1983, art by Bryan Talbot, from "Nightjar" in Yuggoth Cultures #1, 2003) |

The resulting strip is a straightforward thing - mainly a slab of exposition that starts with ten-year-old girl watching her father die, a death that Moore, in typically florid captions, describes as “a dirty death, stumbling and falling amidst the yellow grass and rusted pram wheels, eyes rolling, white foam flecked on blackening lips” as a man the audience is told is the Emperor of all the Birds is “murdered by sorcerers.” The strip then cuts eighteen years later as the girl, Mirrigan Demdyke, receives a lecture from her dying grandmother (memorably depicted by Talbot as an old woman with her eyes sewn shut), who explains that her father was not killed fairly under the rules of magic, as he was not killed by a single opponent, but by a cabal of seven sorcerers conspiring against him. Outraged by this travesty, Mirrigan swears that she will kill the seven, who are introduced at patient length by her grandfather, starting with “Hart Wentworth, whose soul is like a monstrous slug, crusted with sapphires, thrashing contentedly in the tarpit of his own vileness” and ending with Sir Eric Blason, the new Emperor of all the Birds, who Moore leaves relatively undescribed in the comic, but notes in the script is “a member of parliament” with “power on a level that drug-addled ninnies like you and I can scarcely conceive.”

It is not a setup long on subtlety, and the unreconstructed revenge narrative does seem to support Moore’s response to Talbot’s suggestion a few years later that they revive the strip, namely, as Talbot puts it, that Moore had “moved on and was capable of better work,” although to be fair, V for Vendetta ultimately evolved from straightforward revenge narrative to something more interesting, and the possibility certainly exists that Moore would have similarly enlivened Nightjar. Certainly much of the conceptual territory was subsequently revisited, most obviously with, as Talbot points out, with “his concept of an urban sorcerer eventually manifesting itself in the form of John Constantine.” But to both men’s regret, this was as close to a major project together as they ever came.

The underground scene through which Moore and Talbot came up provided another major component of Moore’s shadow career - that work which can be described as stemming out of the Arts Lab scene he participated in between his expulsion from school and the commencement of Roscoe Moscow, a scene that, while it formally wound down in the mid-70s, introduced Moore to a number of creative partners with whom he produced work alongside his early comics career, mostly in the form of a series of bands with varying degrees of extremely minor success. The first and least successful of these was his 1978 effort The Emperors of Ice Cream, with saxophonist Alex Green and, in a near-miss, David J, who answered Moore and Green’s ad in the Northampton Chronicle and Echo, only to ultimately decline due to being invited to join Bauhaus. The Emperors, at least in their first iteration, fizzled, with Green describing them as a “dream band that never got beyond rehearsals,” although Moore would revive the name nearly fifteen years later for a second try.

|

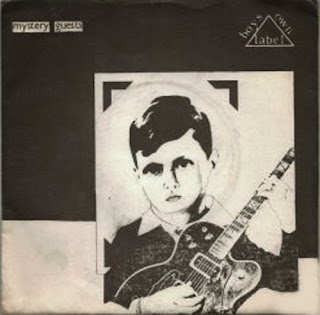

| Figure 778: The Mystery Guests playing live in 1979. (Photo from Bauhaus Gig Guide.) |

More successful were the Mystery Guests, a band which Moore was not actually a member of, but which consisted of several familiar figures from Moore’s orbit, most notably Green and Pickle/Mr. Licquorice, and which Moore wrote some lyrics for. Moore’s description of the band in a 1981 Sounds article is vivid, to say the least, describing the reaction to their music as “violent and schismatic, divided mainly between those who merely loathed them and those who wished them actual physical harm. A few, it must be said, had the wit to appreciate that the abrasive and cruel music, coupled with the sniggering delerium of the lyrics displayed the early thrashings of a monstrous and disturbed genius.” A fanzine review of a concert where they shared a bill with Bauhaus gives a similar sense - the reviewer remarks that “someone told me that they’re excellent musicians in their own right while another source revealed that they’d got a bet on to try and clear the floor (which they almost succeeded in doing).”

|

| Figure 779: The sleeve of the 1980 "Wurlitzer Junction" single, which featured a credit to Curt Vile on the back. |

Moore penned lyrics to one and a half songs for the Mystery Guests. His full song, “Wurlitzer Junction,” which resurfaced from essentially complete obscurity on the Nation of Saints: 50 Years of Northampton Music CD included with the first issue of Dodgem Logic, is an ostentatiously disjointed number that pairs a straightforward punk guitar line with a consciously dissonant keyboard line in the style of a Wurlitzer organ. Moore’s lyrics are oblique, mixing slices of working class life (“I keep the wallets and I stack the tacks behind the factory / I do not do it for remuneration / In fact the lack of tax is actively unsatisfactory”) with moments of slight foreboding (“Why don’t you take me to the imaginary zoo? / You’ll be on the News at Ten / Where ambulance men give empty views”), mixed into an almost but not completely meterless verse. (Moore notes that he’s particularly proud of rhyming “bachelor” and “manufacturer.”) The other, “The Merry Shark You Are,” consists of a first verse written by Moore (“You never hear the bomb that hits you; anesthetic. / Here’s a steady man with thoughts like shrapnel. / You piss in the dark just like / the Merry Shark you are.”) and a second by Mr. Licquorice (“And if she’s dead she died in flames / In cheap hotel rooms where the petrol scent remains / What becomes of slim young women / Born at best on best-forgotten days?”). The two songs were independently released in 1980 where, in Moore’s words, they “immediately soared to the furthermost pinnacles of obscurity.”

A third band, the Sinister Ducks, first formed when Moore, Alex Green, David J, and a fourth member, Glyn Bush (“who happened to be passing through town that particular lunch hour,” as Moore explains) stepped in to fill an afternoon slot for Mr. Liquorice and Moore’s Deadly Fun Hippodrome in the summer of 1979. As Moore describes the experience, “Mr. Liquorice asked me if I could possibly form a super-group and be on stage in ten minutes time. Being pretty drunk, this seemed to me a viable proposition.” A second performance took place two years later at another Mr. Licquorice event, this time actually going as far as preparing material the day before the performance instead of in a ten minute rush. The show was most memorable for a song called “Plastic Man Goes Nuts,” which featured, for a vocal line, the severed head of a talking doll toy that was held up to a microphone rigged to provide post-processing effects while, as David J puts it, “Alan would stare at it with malicious intent. Experimental!”

|

| Figure 780: Kevin O'Neill's cover to "March of the Sinister Ducks." |

After another two years, the band released a single consisting of two tracks, an a-side entitled “March of the Sinister Ducks,” and a b-side consisting of a recording of “Old Gangsters Never Die,” by this point a decade old piece that had already been repurposed once when it was incorporated into the aborted Another Suburban Romance. This is one of two recordings of Moore performing the piece that exists, the other dating from when Moore was a guest on spoken word artist Scroobius Pip’s Distraction Pieces podcast in 2015 and performed it on Pip’s request. Unlike the Sinister Ducks recording, which featured a musical backbeat and saxophone line, and Moore affecting an ostentatious American accent, the Distraction Pieces version is performed without accompaniment, with Moore opting for his natural accent, reworking the narrator from the force of sinister arrogance of the 1983 recording into a quieter figure who seems to almost yearn for the deaths he describes. This change reflects not only the passage of more than forty years since Moore first wrote the piece, but also Moore’s evolving opinion of it, with Moore reflecting that it is “a series of beautiful images relating to old gangster films, old gangster mythology” but that “they don’t actually say very much,” and that “the words exist as a carrier of a kind of mood.” Accordingly, his performance abandons the attempt to define a character, with Moore instead giving individual images room to breathe and stand on their own; indeed, following Moore’s impromptu performance, Pip singles out Moore’s use of pauses and gaps for praise.

|

| Figure 781: A duck. |

“March of the Sinister Ducks,” meanwhile, is an original piece for the single, and is simply one of the most delightfully bizarre things ever produced by the War. It consists of just under three minutes of urgent warnings about the evils of ducks sung over a guitar and piano backing, with Alan Moore contributing both the gregariously baritone vocal line and most of the quacking noises that litter the track. The song steadily develops from its initial ridiculousness, noting that “everyone thinks they’re such sweet little things (ducks, ducks, quack quack, quack quack)” and that “you think they’re cuddly but I think they’re sinister (ducks, ducks, quack quack, quack quack)” before eventually warning about how the ducks are “sneering and whispering and stealing your cars, reading pornography, smoking cigars (ducks, ducks, quack quack, quack quack)” and that “they smirk at your hairstyle and sleep with your wives (ducks, ducks, quack quack, quack quack) dressed in plaid jackets and horrible shoes, getting divorces and turning to booze” before finally proclaiming them “web-footed fascists with mad little eyes (ducks, ducks, quack quack, quack quack).”

But for all that it emerged out of Moore’s art lab connections, the eventual Sinister Ducks single owed no small debt to the comics world as well. The front cover was an inventively bizarre piece by Kevin O’Neill, while the back cover featured the work of Savage Pencil, who shared the comics page of Sounds with Moore. Beyond this, the single also contained an eight page comic adaptation of Old Gangsters Never Die, with art by Lloyd Davis. It’s a bizarre set of collaborators and, for that matter, a bizarre single, utterly unconcerned with any sort of commercial success. Instead, it exists fairly obviously for no reason other than to entertain the people creating it, a monument to nothing save for Alan Moore’s sense of what might be fun.

|

| Figure 782: One of Eddie Campbell's cartoons for "Globetrotting for Agoraphobics." (From Honk #4, 1987) |

This also goes a long way towards describing Moore’s contributions to magazines like Honk, an American anthology published by Fantagraphics. Moore’s contributions include his first work with Eddie Campbell, a three page text piece entitled “Globetrotting for Agoraphobics” for which Campbell provides half a dozen single-panel cartoons as illustration. The piece is a humorous attempt to address “what we can do for agoraphobiacs I our midst. How can we ease their suffering? How can we help them see themselves as useful members of society, rather than as nuisances who get in the way when the Gas-man wants to read the meter in the cupboard under the stairs?” He goes on to suggest that what agoraphobics really need is a trip around the world, which, given the obvious difficulties involved, is, in his account, probably best accomplished by sticking a paper bag over their head and trying to persuade them that they’re on a globetrotting trip without actually taking them outside of their apartment by employing tricks like, in order to get them to think they’re on a plane, sitting “them in an armchair that is situated so as to be facing the wall from less than a foot away, requiring that the knees be tucked up under the chin in an uncomfortable position, where they will remain for the next eight hours.” From there it’s just a small matter of following Moore’s suggestions for specific countries, such as his account of how to recreate Sweden in your kitchen. (“Seating your by-now-world-weary explorer in the chest freezer, fill the sink with blancmange and then try vigorously to unblock it using a conventional plumber’s suction cup while asking them what they think of the live sex show.”)

Moore’s other contribution to Honk is a reprint of a piece earlier published by Knockabout Comics, originally with illustrations by Savage Pencil, although the Honk version was illustrated by Peter Bagge. Entitled “Brasso with Rosie,” the piece is one of the few, and by some margin the earliest openly autobiographical piece that Moore has written. It is, to be sure, an exaggerated and at least partially fictionalized piece - Moore’s claim that an elderly relative of his was once “totally immobilized when a thoughtless spouse decided to hang mirrors upon either side of the tiny, damp-scented room in which he customarily sat, presenting the luckless dotard with an infinite succession of doppelgangers arrayed to either side of him,” leading him to believe that he had “been granted some form of X-ray vision, enabling him to see through the peeling walls and into the identical living rooms of his neighbors,” and that “he remained like this for twenty years” is, for example, surely overstating the case by at least half a decade. [continued]