The omnibus version of this chapter will be sent to backers in the next week or two.

Previously in The Last War in Albion:The god of Watchmen was revealed to be comprised of negative space; a tangible lack within it; a gap that demands to be filled in on the map of its psychic territory, to be named and outlined, as though doing so will finally, at last, serve to snap all the pieces into place and explain everything.

This is, perhaps, why so much ink has been spilled within the War on attempts to argue that this gap, in effect, does not exist - that Watchmen can be understood purely, or at least primarily, in terms of its influences, thus allowing those living in its wake to exist as though they are free from its vast and monolithic splendor. It is, after all, the easier option; it does not require staring too long at the cavernous depths within. It gives the comforting illusion that Watchmen is, at its heart, an easily solved mystery - a question with a definite answer. Nothing could be further from the truth, but for those who would otherwise find themselves caught in its blast, reduced to mere shadows cast by its incinerating radiance the idea that the book is simply some inevitable consequence of what came before is a useful delusion.

There are, of course, other factors involved in the particular obsession with Watchmen’s influences, most notably the fact that Moore and Gibbons have both asserted consistently that Watchmen was envisioned as a creator-owned book, a claim that makes the degree to which its ideas originated with Moore and Gibbons relevant. More broadly, the fact that Moore has made a number of provocative statements about the ways in which DC Comics and, more specifically, Grant Morrison have profited off of the recycling of his ideas has led to a small cottage industry in attempting to demonstrate Moore’s hypocrisy. And since Watchmen is both Moore’s most prestigious work and one with several well-documented influences, it has long been Exhibit A for these attempts.

Most attempts to argue that Watchmen can be explained primarily in terms of its influences have focused on its relationship with characters DC acquired from the failing Charlton Comics. As a company, Charlton was formed in 1944, and published comics in a number of genres. But for the purposes of Watchmen, only six of Charlton’s characters are actually relevant: Captain Atom, Thunderbolt, the Blue Beetle, the Question, the Peacemaker, and Nightshade. These characters come from a fairly narrow set of sources. Three of them - the Peacemaker, Nightshade, and Captain Atom were created by the astonishingly prolific Joe Gill, the latter two alongside Spider-Man co-creator Steve Ditko, who also created the Question. They also generally originated in a fairly narrow band of time - Thunderbolt, Nightshade, and the Peacemaker all debuted in 1966, while the Question debuted in 1967 and Captain Atom in 1960. Only the Blue Beetle forms something of an exception, having existed in two forms - a Golden Age version that predated Charlton, created by Charles Nicholas Wojtkoski in 1939 for Fox Comics, and the Silver Age version created for Charlton in 1966 by Steve Ditko.

|

| Figure 867: The Shield, who was the original character Moore intended to use for the role that eventually became the Comedian, first appeared in Pep Comics in 1939. |

The relationship between Watchmen and these six characters is both well-documented and oft-misrepresented. In the eyes of his detractors, Moore’s contribution to Watchmen amounted to little more than changing the names of some obscure 60s superheroes, as in Dan Slott’s suggestion that “the real Before Watchmen comic would show Alan Moore reading stacks of Charlton comics.” Put bluntly, this is ridiculous. It is true that Moore’s first proposal to DC for what became Watchmen was titled Who Killed the Peacemaker, and made use of the Charlton characters. This was not, however, the earliest iteration of the story in the general case. As Moore puts it, he’d had “a vague story idea” along the lines of Watchmen in mind for years, based on the idea “that it would be quite interesting to take a group of innocent, happy-go-lucky superheroes like, say, the Archie Comics super-heroes, and suddenly drop them into a realistic and credible world,” noting that his “original idea had started off with the dead body of the Shield being pulled out of a river somewhere.” Then, while batting around ideas for a mooted DC project with Dave Gibbons, with whom he’d worked numerous times on 2000 AD, Moore found out that the Charlton characters had been recently acquired by DC and began developing the idea in detail with them, only to have DC ask him to rework it with original characters when it became obvious that Moore’s take was going to render the Charlton characters unsuitable for further use within DC.

But, crucially, the entire reason for using the Charlton characters was that they, like the suite of Archie Comics superheroes he’d originally had in mind, were, in Moore’s words, “third-string heroes,” as opposed to “iconic figures like Superman, Batman, and Captain America.” In other words, the entire point of the exercise was that it would make use of characters who were effectively blank slates onto whom Moore could project whatever he wanted. The Charlton characters’ influence was, in practice, the complete and utter absence of any high quality, classic stories that might require any sort of substantive or direct engagement. Their influence is in many crucial regards almost an anti-influence, based primarily on the fact that the heroes are so anodyne as to impart little to a story save for the basic fact that they are historically existent superheroes.

|

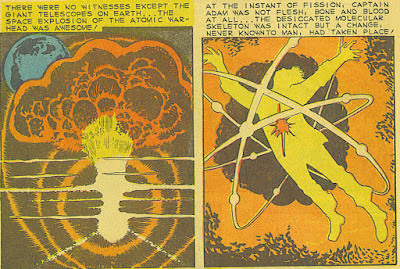

| Figure 868: The origin of Captain Atom. (Written by Joe Gill and Steve Ditko, art by Steve Ditko, from, Space Adventures #33, 1960) |

That said, there are numerous plot points within Watchmen that clearly exist because the project was developed with the Charlton characters in mind. The fact that Doctor Manhattan’s powers are based in imagery of nuclear power, for instance, is clearly a legacy of Captain Atom, whose origin also involved being disintegrated and reincorporated. Similarly, the idea of there being two versions of Night Owl, the first a cop, the second a brilliant inventor, clearly originates in the publication history of the Blue Beetle, whose two incarnations have similar origins. Other small plot details such as the relationship between Doctor Manhattan and Silk Spectre also clearly originate in the details of the Charlton characters. In other words, even though Moore’s initial idea for Watchmen predated the idea of doing it with the Charlton characters, it’s undeniably the case that Watchmen, in its finished form, was influenced by the fact that it spent a period being developed as a revamp of six characters previously owned by Charlton Comics.

|

| Figure 869: The uncomplicated patriotism of Captain Atom. (Written by Joe Gill, art by Steve Ditko, from Space Adventures #38, 1960) |

Equally, however, it’s clear that Moore was always interested in what Charlton didn’t do. His oft-reprinted pitch using the Charlton characters, for instance, focuses heavily on the psychology of the character, musing, “try to imagine what it would be like to be Captain America. The desk you’re sitting at and the chair you’re sitting on give less of an impression of reality and solidity to you if you know that you can walk through them as if they weren’t there at all. Everything around you is somehow more insubstantial and ghostly, including the people that you know and love.” This, it should be stressed, is not a theme that is substantively explored in Joe Gill’s original Captain Atom stories in Space Adventures, which are entirely unconcerned with the character’s interiority. More importantly, Moore highlights his unfamiliarity with the character when discussing this theme, noting that he “can’t remember if the Captain had a human love-interest back in those early days before Nightshade, but let’s say that he had, for the sake of argument. She is now forty-four, and she looks and feels forty-four as well. The young man that once she loved and possibly slept with is still as youthful and virile as ever, and it’s she who has aged and started past her prime. How would she feel about that? How would Captain Atom feel watching her grow old and eventually die while he remained the same constantly?” (Indeed, in a fact never remarked upon when Moore’s detractors bring up the Charlton characters, Moore openly admits in the Charlton pitch that “there are large amounts of the details concerning the Charlton characters that I’m simply unfamiliar with,” explaining that “there were hardly any comic shops over here in the Sixties, and I had to rely entirely upon the incredibly spotty newsstand distribution. On top of this, I had foolishly bound all of my beloved Charlton material into a book and then lent it to someone who I never saw again. As a result, most of the character details that I have built upon below are based upon my unreliable memory.”) Moore’s discussion of how Captain Atom would alter the geopolitical scene is similarly based in an active reaction against the actual Charlton material, in which Captain Atom is an uncomplicatedly jingoistic figure, generally suggesting that the best solution to the nuclear arm’s race would be if the United States won it, a situation that, in Joe Gill’s world, would be an unalloyed good.

|

| Figure 870: The Peacemaker is defined largely by his reluctance to engage in violence. (Written by Joe Gill, art by Pat Boyette, from Fightin' 5 #40, 1966) |

More to the point, however, it’s clear that the decision to abandon the Charlton characters gave the project a significant creative jolt, especially with regards to the Comedian and Silk Spectre, who Moore evolves considerably from their original inspirations. When writing about Nightshade in the Charlton pitch, for example, Moore openly admits that “she’s the one I know the least about and have the least ideas on,” save for a vague desire to explore the idea of superhero sexuality in terms of her. It’s not until he creates Silk Spectre that the character begins to have any significant distinguishing characteristics, as she becomes “another second-generation super-hero similar to the new Nite-Owl,” a concept with no antecedent in Nightshade, and which forms the core of the actual Watchmen character. Similarly, Moore notes that the Comedian is “the most radically different of all our new characters to the original,” which is a considerable understatement. Joe Gill and Pat Boyette’s Peacemaker is an avowed pacifist defined by his use of non-lethal weaponry. The Comedian, on the other hand, is an openly nihilistic figure who clearly enjoys violence, a concept that is not so much based on the Peacemaker as it is the outright opposite.

|

| Figure 871: The uncompromisingly moralistic philosophic monologue is a key part of Mr. A. (By Steve Ditko, from witzend #4, 1968) |

But there is one area in which the relationship between the Charlton material and Watchmen is more complex and worth delving into, which is the evolution of Rorschach from Steve Ditko’s The Question. In the Charlton pitch, Moore talks about how the Question “is concerned with Truth and Morality, and if that means breaking corrupt laws that only exist because of the actions of dissident pressure groups and minorities, then he will break them without thinking about it.” This, at least, is well-grounded in the original comics, where the Question’s alter-ego was the crusading journalist Vic Sage, who repeatedly refuses to back down from investigating corruption no matter how much pressure is put on him and the station he works for. But in citing the strict line between good and evil, Moore is drawing as much from another Ditko-created character of the period, namely Mr. A, who Ditko created for Wally Wood’s underground book witzend, and who the Question was designed as a Comics Code-acceptable version of. Like the Question, Mr. A is a journalist/vigilante hero, but where the Question is generally written as a example of moral rightness, Mr. A stories are long on explicit lectures about the nature of good and evil. The first Mr. A comic, for instance, opens with Mr. A proclaiming, “fools will tell you that there can be no honest person! That there are no blacks or whites… that everyone is gray! But if there are no blacks or whites, there cannot even be a gray… since grayness is just a mixture of black and white! So when one knows what is black, evil, and what is white, good, there can be no justification for choosing any part of evil! Those who do so choose are not gray but black and evil… and they will be treated accordingly,” an opening that’s clearly what Moore is riffing on when, in “At Midnight All The Agents,” he has Rorschach declare that “there is good and there is evil, and evil must be punished. Even in the face of armageddon I shall not compromise in this.”

But there is more to this than might be immediately apparent. [continued]