-pic.jpg) |

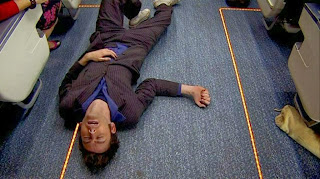

| Such a heavenly way to die |

I completely forgot to do the images for the next Last War in Albion before 4am, so I'm running that Friday and this today.

It’s June 14th, 2008. Mint Royale are at number one with “Singin’ in the Rain,” with Sara Bareilles, Duffy, Rihanna, and Ne-Yo also charting. In news, Euro 2008 is unfolding in Austria and Switzerland without England’s involvement. Apple introduces the iPhone 3G. The US Supreme Court decides Boumediene v. Bush, which ruled that foreign terrorism suspects in Guantanamo Bay could offer habeas corpus petitions in US courts. And massive floods break out in Iowa.

While on television, it’s Midnight. There is a school of thought that, not unreasonably, views Midnight as the greatest script Russell T Davies ever wrote for Doctor Who. It is not that this view is inaccurate so much as that it is a claim that often has a wealth of unseen premises. To be sure, Midnight is very good - a blend of creepiness and furious cynicism with real bite. But often the praise for it seems to tacitly be criticism of, well, essentially every other Davies episode. Midnight has few jokes, an ending that’s the polar opposite of “the power of love,” and, more broadly, is clearly Davies writing to push himself and get out of some of his ordinary tropes. In other words, it’s seemingly a Davies script for people who don’t like Davies scripts.

It is true that there is something strange about Midnight. Reading The Writer’s Tale, one gets the feeling that it’s an almost hallucinatory experience. According to the dates in The Writer’s Tale, on September 27th, 2007 Davies determined that the planned script for what was then episode eight of Season Four (it got moved late in production) wasn’t working out. On October 5th, after finishing rewrites to the Sontaran two-parter, Davies tells Cook that he’s thinking of writing it, though he frets about the time he has to do it in. Five days later, on Wednesday the 10th, he mentions to Cook the basic outline of it - everyone trapped in a bus (to save money) and a monster on the outside that possesses a woman (to be called Sky) who begins repeating people. What appeals to him, it seems, is both the creepiness and the fact that it would be technically difficult to shoot but very cheap - he speaks of “all that production-tension creeping onto the screen,” and about it being a story where the Doctor loses his speech. But he also admits that he has no idea how it ends.

That Saturday he clears the weekend to work on it, with the goal of starting production on Monday if the script works out. The weekend is a buzz of e-mails between them in which Davies describes the intensity of writing it. He tells Cook about the difficulty of juggling eight person scenes, and says that his “brain is bleeding,” but less than ten hours later It’s “buzzing” and he’s having trouble keeping all his ideas in check. He hands the script in on Monday, and Julie Gardner and Phil Collinson love it. He sits down with it again on Wednesday, and finishes it up that evening, and that’s that. From idea to script in just about a week.

The way in which the script seems to have haunted its writer comes out in the story itself, which advances with a sort of dizzying anxiety that seems to just spill out of nowhere. The nature of the season structure and of the story’s promotion allowed this one to be a bit of a sleeper; the preview teased the basic “people stuck on a bus and a monster knocking,” but gave no particular indication of the story’s hook. Sandwiched as it was between the big Rose Tyler return in Turn Left and the Moffat era’s Episode Zero, this story looked innocuous. The degree to which it actively, angrily challenges basic premises of Doctor Who wasn’t clear, so that the way in which the bus turned toxic was scary and unnerving in a way that can’t quite be captured outside the context of 2008.

It’s also oddly to this story’s benefit that it was eventually moved to go after Silence in the Library/Forest of the Dead and thus after the announcement that Moffat was the incoming showrunner. Because for all that this story is unlike other Davies scripts, it’s very much like a Moffat script in several regards. This is the first time that Davies has really attempted a straight horror script (Tooth and Claw not having gone for fear), a format usually associated with Moffat. On top of that, the repeated speech technique feels very much like a Moffat invention. Moffat is often described as being fascinated by repeated catchphrases, but it’s more accurate to say that he’s fascinated by glitches in communications media - he rarely does repeated phrases that are not based on some piece of technology that isn’t working quite right. In many ways Davies takes that approach to its most extreme level, having the phenomenon of language itself become a technological glitch through which repetition takes place.

It’s interesting, then, that this appropriation of Moffat’s iconography should come in such a pessimistic story. One could, if one was feeling snarky, suggest that this was some sort of swipe at what Davies perceived the Moffat era would be, perhaps picking up on About Time’s claim that Davies wanted the show to end when he left. But this is almost certainly nonsense - any perceived tension between Davies and Moffat is, in reality, the invention of partisan fandom picking fights where none exist. If Davies is playing with Moffat’s iconography he is doing so out of respect - trying to tell his version of a Moffat story, and reasonably so, given that Moffat will, inevitably, be doing his versions of Davies stories in years to come.

And this is unmistakably a Davies story, in the end. For all that its pessimism may seem jarring in the context of Davies’s other Doctor Who, it’s very much him. He admits, talking to Ben Cook, that the story a conscious inversion of Voyage of the Damned’s band of plucky survivors, instead featuring “humans at their worst. All paranoid and terrified. Much closer to the real world - or my view of the world.” Which makes sense. The Davies of Aliens of London/World War III, with his cynical, furious satire of the Iraq War was always closer to what one would have expected Davies-penned Doctor Who to be than what we got, which was an altogether more optimistic show. The entire Eccleston series, in fact, had a vein of anger running through it that mostly drained out in the Tennant era as the show became confident in its success.

Tennant’s story arc is, as we noted at the start of his era, one based around that theme of confidence and hubris. It is almost certainly coincidental, but nevertheless chillingly fitting that this story features a moment where the creature knocks on the side of the bus four times. Because it is this story in which the theme of the Doctor’s hubris becomes fully pronounced. It’s not just, in the end, that the people on the bus let the Doctor down. It’s also a story in which all of the Doctor’s skills turn against him. His absolute refusal to throw Sky off the bus becomes uncompromising arrogance that only worsens the situation. His enthusiasm and curiosity become a source of disgust as the other passengers accuse him of having fun. Even his intelligence becomes a handicap, his declaration that he’s “clever” (the same word he uses to describe Rattigan in The Sontaran Stratagem/The Poison Sky) becomes just another sign of his arrogance. Beyond that, of course, there’s the fact that his words are literally turned against him in the course of the story.

And so we get a story where the Doctor loses. Indeed, his presence makes it worse. The end solution - throwing Sky out of the bus - is exactly what the passengers proposed in the first place. The Doctor had nothing to do with the resolution, having been incapacitated by that point. The only difference his presence actually caused was that the Hostess died too because nobody threw Sky out early on. This is, seemingly, not the point Davies meant to make, as it’s ultimately quite xenophobic, and yet it’s there, quietly undermining the idea that all that’s going on is that the people on the bus are the worst of humanity.

Indeed, there are ways in which the people on the bus are closer to the Doctor than one might expect. Professor Hobbes, in particular, is a clear mirror of the Doctor, complete with his own companion. To be sure, he’s a flawed mirror. He’s cruelly dismissive of his companion, and there’s the quiet implication that he’s taken her along not to foster her talent but because he finds her attractive. And he’s studiously close-minded, rejecting things as impossible instead of reveling in possibilities. Nevertheless, the synonyms of title are clear. And, of course, he’s played by Patrick Troughton’s son, which, while an accident (Troughton was cast two days before production started when the original actor broke his leg) hammers home the parallels.

And opposite the mirror of the Doctor and his companion we get a mirror of the audience - Biff, Val, and Jethro being the ordinary “family” audience that might be expected to be watching Doctor Who. Yes, Jethro’s a bit old, but that’s kind of the point. If this is supposed to be a broken and flawed mirror of the audience it’s entirely fitting that the kid should be jaded and cynical and “too old” for Doctor Who, just as the mother and father show themselves to be flawed, hypocritical, and violent characters. It’s not some random bunch of people who are flawed and doomed here, but a specific set of characters who invoke and mirror the Doctor.

So what we have is not a situation where the Doctor simply fails, but one in which there is, quietly and without fanfare, a narrative collapse that isn’t averted. The underlying premise of Doctor Who simply falls out and breaks down. The Doctor doesn’t make things better. He doesn’t save the day. The world is simply a cruel and vicious place. As, in Midnight, it literally is - a planet that it is impossible to survive on, and on which human habitation is simply terribly ill-advised. People shouldn’t be here at all. This, at least, contains the narrative collapse - it’s allowed to exist within the specifically hostile space of the planet Midnight. Nevertheless, within this space we find out that Doctor Who stories simply cannot function at all.

This is something radical and new. Not even in The Impossible Planet/The Satan Pit did we get a story in which it was suggested that Doctor Who as a series simply could not function in certain spaces. Sure, we got an abyssal horror, but the Doctor and indomitable humanity still won the day. That story only alluded to a death drive, and tied it to fandom. This is something else - a situation in which the Doctor simply doesn’t work. This is, to be fair, an existing subgenre in action-adventure serials. But typically, when they do stories where the hero is completely helpless the hero is impotent in the face of real-world horrors like famine or cancer or 9/11 (superhero comics, in particular, had a brief period where everybody did astonishingly bad pieces about how superheroes couldn’t stop 9/11). This subgenre amounts to mawkish glurge in which the fact that stories are fiction is treated as a flaw, and anybody who writes it should be punched. (Note: This proposal would likely prove fatal to J. Michael Straczynski.) Midnight does something markedly different, creating a situation in which the hero is powerless not because of something that exists in the real world that it would be tacky for the hero to trivially stop but because of something that is wholly a part of the fiction. The Doctor is defined as the sort of character who should save the day in exactly the sort of situation that Midnight puts him in.

And while the story quietly displaces this tension onto the planet, suggesting that it’s only within the confines of this eccentric space that Doctor Who fails. But the story hints at the real and darker truth. It’s not Midnight that renders the Doctor helpless, but the reality of people. The dark mirrors of the Doctor aren’t twisted in the way that the Master is - simple inversions of all that he is. They’re dark mirrors because they’re ordinary, flawed people - the same view of humanity that we get in Utopia. They’re vivid portrayals of the myth of Doctor Who transported into everyday people, of the sort that Davies writes very, very well. And they break the show. In a wonderfully disturbing inversion of the mawkish glurge that usually constitutes the hero being utterly impotent in the face of a threat, it is not that the hero is flawed because he’s fictional. It’s that we are all flawed because we are not.