This is the fifth of seven parts of Chapter Four of The Last War in Albion, covering Alan Moore's work onDoctor Who and Star Wars from 1980-81. An ebook omnibus of all seven parts, sans images, is available in ebook form from Amazon, Amazon UK, and Smashwords for $2.99. The ebook contains a coupon code you can use to get my recent book A Golden Thread: An Unofficial Critical History of Wonder Woman for $3 off on Smashwords (the code's at the end of the introduction). It's a deal so good you make a penny off of it. If you enjoy the project, please consider buying a copy of the omnibus to help support it.

“So this Zealot comes to my door, all glazed eyes and clean reproductive organs, asking me if I ever think about God. So I tell him I killed God. I tracked God down like a rabid dog, hacked off his legs with a hedge trimmer, raped him with a corncob, and boiled off his corpse in an acid bath. So he pulls an alternating-current taser on me and tells me that only the Official Serbian Church of Tesla can save my polyphase intrinsic electric field, known to non-engineers as "the soul." So I hit him. What would you do?” - Warren Ellis, Transmetropolitan

PREVIOUSLY IN THE LAST WAR IN ALBION: Alan Moore wrote some clever comics about Doctor Who, including the beginning of an abandoned epic involving a war unfolding non-chronologically such that the first attack precedes the incident that sparked the war...

|

| Figure 163: Alan Moore's reputation for fights is often a part of more caricatured depictions of him. |

Moore was, apparently, intending to further flesh out his idea of a non-chronological war further, but circumstances intervened. Instead left the title along with Steve Moore, who had worked extensively on a plot outline for a third Abslom Daak story only to discover that the editor, Alan McKenzie, had already begun writing a story with the characters. Angered by this, Steve Moore abruptly quit the main title and was replaced by Steve Parkhouse, and Alan Moore followed suit in what Steve Moore has referred to as “a wonderful gesture of support that was remarkable for someone at that early a stage in their career.” While it’s true that Moore, who had not come close to establishing himself as a writer, took a genuine professional risk in quitting, the fact that he did so early in his career is the only remarkable thing here. It is, in fact, the first of many such gestures in his career. Moore has, within comics, become almost as famous for his tendency to get into professional feuds as he has for his comics work. Indeed, Moore’s capacity for umbrage is ultimately one of the primary casus belli of the War.

It is worth, then, looking at this first dispute in order to better understand the nature of Moore’s umbrage. First of all, this dispute is interesting in that there is no way to frame it as being over a slight to Moore himself. He left purely in solidarity with his friend. It is very difficult to frame Moore’s actions as anything other than a genuine principled stand, taken at, if not great cost to himself, at least significant risk. This, at least, is characteristic of all of Moore’s feuds and disputes; it is difficult to think of any in which he has materially benefitted from his stance. The archetypal Alan Moore feud is one in which Moore furiously leaves money, often quite large amounts of it, on the table in pursuit of subtler ideological goals.

This highlights the second interesting part of the dispute, which is the nature of the objection. It is manifestly not that McKenzie was using Steve Moore’s characters without his permission. Steve Moore was well aware that he didn’t own Daak or his fellow Star Tigers. He had no objection to the characters being dusted off eight years later, although he notes that he appreciated that Richard Starkings, the then-editor of Doctor Who Magazine, asked him if he’d mind Daak coming back before proceeding with the story. Moore was well aware that he was working on other people’s property and that they could continue his work without him; as he says, “no one in mainstream British comics owned the characters they created, and Daak and the Star Tigers were always going to belong to Marvel.”

Rather, the objection was to allowing Moore to waste time developing a Daak story only to find out that the editor who had given him the task had quietly stolen the work for himself without telling him. There’s a subtle distinction here, which is characteristic of many of Alan Moore’s disputes. It does not hinge on a question of what the McKenzie was legally allowed to do, but rather on the fact that McKenzie behaved in a manner that struck both Moores as dishonest and deceitful. This is a key facet in Moore’s disputes, and one that is often lost on his critics. Moore rarely objects to specific practices so much as he objects to people who change the rules on him when he feels he’s upheld his side of a bargain. This fact often gives his disputes an oddly disproportionate character, and explains what can otherwise seem like Moore’s erratic behavior during them, with Moore objecting vigorously to what often seem like minor slights. What appear in many cases to be professional disputes are, in practice, deeply personal grievances based in Moore’s belief that someone he had trusted betrayed him. The implications and causes of this odd tendency will become clearer over the course of the War.

|

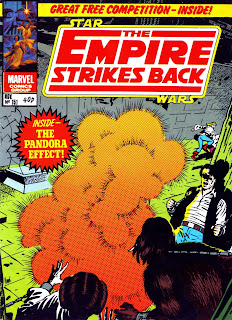

| Figure 165: Alan Moore's first Star Wars strip, "The Pandora Effect," appeared in The Empire Strikes Back Monthly #151 (cover artist uncredited, 1981) |

Still, in the case of Doctor Who Monthly the dispute was ultimately minor. Moore left one publication and almost immediately took up work at the same company on another title in what was by and large a like-for-like substitution whereby he found himself writing five-page backup features about a different major science fiction franchise. This time it was Star Wars, specifically The Empire Strikes Back Monthly.

There are few external events as significant to the War as the 1977 release of George Lucas’s science fiction epic Star Wars. The movie almost single-handedly changed both the default aesthetics of science fiction and the economic climate in which science fiction was made, not only in film, but in other media. From a business perspective, Star Wars is a dividing line in the history of film. The boom in sci-fi/fantasy film that started in the late 1970s is almost entirely due to the impact of Star Wars, which grossed what was a then-staggering $300m, nearly double what the next highest grossing film (Close Encounters of the Third Kind) made. From that point on, science fiction was box office gold. But the film’s real impact came from George Lucas’s decision to take a half-million dollar cut in his fee for directing the film in favor of retaining the merchandising rights, which he exploited ruthlessly. First he ginned up interest in the movie by getting the novelization and the first issues of the Marvel Comics version of the film out ahead of the film’s release.

|

| Figure 166: Marvel Comics'Star Wars adaptation was major business for the company, and a hugely successful promotion for the film (Howard Chaykin, 1977) |

This alone was a big deal. The American comics industry was in rocky shape in the late 1970s, and the success of Marvel’s Star Wars adaptation was credited by Jim Shooter, who took over as Editor-in-Chief in the 1980s, for keeping the company afloat, crediting Roy Thomas, who secured the rights for Marvel, with single-handedly saving the company. Even more significant, however, was the toy line, the license for which went to Kenner. The toys were so popular that Kenner was hopelessly swamped by demand, and spent Christmas 1977 selling certificates that could be redeemed for toys in the new year. That year the toys were so successful that, if they were a film, their gross sales would have made them the fifth biggest of the year.

Star Wars, in other words, was not merely a successful film. It created the idea of science fiction films as a large-scale franchise. This was not an entirely original idea - Gerry Anderson spent the 1960s and early 70s running a small television empire based on promoting his shows in multiple media, making sure to have official comics magazines and the like that tied in and advertised the shows. But Star Wars brought things to a new level. The larger franchise of toys, comics, books, and, with later films, every other sort of merchandise imaginable became bigger sources of income than the films themselves, such that a new film was in many ways simply an advertisement for the much larger set of marketing it inspired. This was the logic under which Doctor Who acquired its own comics magazine, and was similarly the logic under which The Empire Strikes Back Weekly (later The Empire Strikes Back Monthly) existed as well. In short, science fiction properties weren’t just texts in their own right; they were big business in their own right.

But Star Wars had another sort of influence that was largely aesthetic. This is usually described in terms of a shift towards big-budget, special effects laden blockbusters. This is true, but in many ways just a subset of a larger issue. The real aesthetic shift that Star Wars offers is that it is the last nail in the coffin of science fiction as a genre in the sense of plot structure, as opposed to as a genre in the sense of a given iconography. There was a brief moment, generally referred to as the Golden Age of Science Fiction, in which science fiction stories tended to amount to logic problems. This era is encapsulated by the definition writer Theodore Sturgeon gave for science fiction when he said, “a science fiction story is a story built around human beings, with a human problem, and a human solution, which would not have happened at all without its scientific content.” This definition, intriguing as it is, described a wealth of stories that often boiled down into one of two categories. The first are basically logic puzzles, in which some technological snafu is solved through clever thinking about well-defined rules. The canonical example is Isaac Asimov’s novel/short story collection I, Robot, in which basically all of the stories take this tact, playing with Asimov’s invention of the “Three Laws of Robotics,” which state, in order, that a robot can never allow a human to be hurt, must always obey humans, and must protect its own existence, with each law being trumped by the preceding one(s). So in the story “Runaround,” for instance, a particularly expensive robot who has been put in a peculiar situation whereby a particularly casually given command conflicts with a third law that has been bolstered in the robot so that “his allergy to danger is unusually high,” resulting in a sort of feedback loop that the robot cannot escape from. The solution, of course, is for one of the human characters to throw themselves in danger in the presence of the robot, thus triggering the sacrosanct First Law of Robotics and breaking the robot from its cycle.

| Figure 167: The Golden Age of Science Fiction had an iconic artistic style... (Hubert Roberts, Astounding Science Fiction 28.6, 1942) |

The other sort of story can be described as thought experiments. On the short story level they include things like Arthur C. Clarke’s “The Star,” which tells the story of an expedition exploring the remnants of a supernova and discovering a scorched planet with the ruins of a civilization in its orbit. The story is a straightforward twist ending piece, continuing for roughly 2500 words of the narrator, a futuristic Jesuit monk, describing the expedition and its discovery of some awful truth that will shake the Catholic faith to its core. In the final paragraph it’s revealed that the narrator has successfully dated the explosion of the supernova. Clarke writes, “There can be no reasonable doubt: the ancient mystery is solved at last. Yet, oh God, there were so many stars you could have used. What was the need to give these people to the fire, that the symbol of their passing might shine above Bethlehem?” But this structure is suitable for more than just twist ending short stories; Walter M. Miller’s acclaimed A Canticle for Leibowitz holds to the same basic structure, imagining a monastic community after a nuclear war has devastated the world, pouring over memorabilia and artifacts of the world and interpreting detritus like shopping lists as holy relics. The story has numerous moments of moving humanity, but its sheer scope - the novel takes place over 1200 years - means that it cannot be treated as a character piece. It is instead an imagined history - an attempt not to tell a story about people but about what might happen following a particular set of events.

Both types of stories were, if not unique to science fiction as a genre, at least distinct narrative forms that existed on their own terms. They were neither the episodic and epic-derived structure of other stories in the pulp-derived magazines they were often first published in nor the tightly wound literary structure that derives from Aristotelean tragedy. They were also, however, a vanishingly brief moment in literary history, belonging squarely to the dreams of technocratic utopia that flourished in the aftermath of World War II. The 1960s New Wave of science fiction writers like Michael Moorcock and J.G. Ballard challenged it thoroughly, and the style was on the wane for decades. What Star Wars did was not so much to reject the style anew as to provide a credible alternative, where science fiction became an iconography for straight-up pulp adventure. Much of Star Wars could just as easily be done as a sword-and-sorcery epic (indeed, the interchangeability of the two plots was the underlying premise of D.C. Thompson’s Starblazer) or as a swashbuckling pirate story.

|

| Figure 168: ...which George Lucas unabashedly appropriated for his film. |

In this regard what is significant is not so much that Star Wars was full of visual spectacle, but that the visual spectacle was often a direct homage to the vibrant cover art of old pulp sci-fi magazines. The irony here is considerable - the film that finally killed off the Golden Age aesthetic for good did so by mimicking the cover art of the very magazines that had housed much of the Golden Age. There are moments in Star Wars where one can practically identify the exact cover of Astounding Science Fiction that inspired the shot. But the genius of Star Wars was not simply in its use of visual spectacle. What Star Wars did was to take the plot elements of the pulp epic and fit them together into a film with a compelling storyline that hung together like literary fiction. The way it did this was by using a plot structure called “the hero’s journey” established by Joseph Campbell in his book The Hero With A Thousand Faces.

On one level Campbell was a critic not unlike Vladimir Propp, in that he argued for the existence of a single plot structure that described a large number of stories. But while Propp was content to describe Russian folk tales and Russian folk tales alone, Campbell’s ambition is nothing short of describing the overall structure of all mythology. His underlying structure is a simple one involving a hero receiving the “call to adventure,” encountering a series of obstacles and encounters, the culminating set of which are, in Campbell’s telling, the Meeting with the Goddess, the Atonement with the Father, and Apotheosis.

|

| Figure 169: The spirit of Binah in her aspect as Marie (Alan Moore and J.H. Williams III, Promethea #21, 2002) |

Campbell describes all of these in his characteristically flowery language. The Meeting with the Goddess, for instance, is “a mystical marriage of the triumphant hero-soul with the Queen Goddess of the World” that is “the crisis at the nadir, the zenith, or at the uttermost edge of the earth, at the central point of the cosmos, in the tabernacle of the temple, or within the darkness of the deepest chamber of the heart.” The figure is a sort of sacred feminine akin to what is represented Kabbalistically in the Sephirah of Binah, or Understanding. Campbell’s description of one manifestation, the Lady of the House of Sleep, is telling: “She is the paragon of all paragons of beauty, the reply to all desire, the bliss-bestowing goal of every hero’s earthly and unearthly quest. She is mother, sister, mistress, bride. Whatever in the world has lured, whatever has seemed to promise joy, has been premonitory of her existence… Time sealed her away, yet she is dwelling still, like one who sleeps in timelessness, at the bottom of the timeless sea.” This invocation of the sea closely mirrors Dion Fortune’s description of Binah as “the Great Mother, sometimes also called Marah, the Great Sea… She is the archetypal womb through which life comes into manifestation.”

Within Campbell, however, this event is paralleled by another immediately after, which Campbell calls Woman as the Temptress. After encountering the Goddess there comes a point where women “become the symbols no longer of victory but of defeat,” for “no longer can the hero rest in innocence with the goddess of the flesh; for she is become the queen of sin.” This evokes the virgin/whore complex at the heart of many depictions of the sacred feminine, and captured chillingly in the revelation given to Edward Kelley while scrying in the seventh aethyr that drove him to abandon magic: [continued]