![]() |

| Figure 613: William Godwin |

He turns also to Mikhail Bakunin’s Collectivist Anarchism, with was an important predecessor to Marxism, along with Peter Kropotkin’s rejection of private property, and, more contemporarily, Hakim Bey (who in addition to being an anarchist and pedophilia advocate was an open sorcerer, defining the concept as “the systematic cultivation of enhanced consciousness or non-ordinary awareness and its deployment in the world of deeds and objects to bring about desired results”). But for the purposes of understanding Blake, perhaps the most important thinker Moore touches upon is William Godwin, whose Political Justice, in Moore’s account, advocated “that the individual act according to his or her individual judgement while allowing every single other individual the same liberty.”

![]() |

Figure 614: One of Blake's illustrations

for Mary Wollstonecraft's Original Stories

from Real Life. (1791) |

Political Justice, more properly titled Enquiry Concerning Political Justice and its Influence on Morals and Happiness, was published in 1793, the same year as America a Prophecy, and Godwin and Blake traveled in similar circles - Blake did a series of illustrations for Godwin’s future wife Mary Wollstonecraft’s Original Stories from Real Life in 1791, for instance. (Godwin and Wollstonecraft’s daughter, also named Mary, would go on to have a significant career of her own, largely under her married name, acquired from “Ozymandias” poet Percy Bysshe Shelley.) Blake followed Godwin no more than he did any other man, but the intellectual similarities are clear enough.

![]() |

Figure 615: The cover for the third issue

of The Northampton Arts Group Magazine,

featuring an iteration of Alan Moore's concept

for "the Doll." (c. 1973) |

For Moore’s part, at least in terms of V for Vendetta, the most obvious anarchist to mention is Colin Ward, whose Anarchy in Action was first published in 1973, when Moore was working with the Northampton Arts Group, putting out zines while writing spoken word pieces like “Old Gangsters Never Die,” submitting a doomed proposal for “a freakish terrorist in white-face make-up who traded under the name of the Doll and waged war upon a totalitarian state sometime in the late 1980s” to future Starblazer publisher DC Thomson, dreaming up his sci-fi epic Sun Dodgers and the character of Five, “a mental patient of undefined but unusual abilities who had been kept in a particular room, room five,” and meeting Phyllis Dixon, who he quickly married the next year. Ward offers a summary of anarchist thought on a wealth of issues, including specific topics like housing and education, packaged as anavuncular sales pitch. (His preface begins, “how would you feel if you discovered that the society in which you would really like to live was already here, apart from a few little, local difficulties like exploitation, war, dictatorship, and starvation?”) Certainly Ward’s thought coincides with Moore’s in plenty of places - his blunt summary of the contemporary education system as being akin to that of ancient Sparta - “training for infantry warfare and for instructing the citizens in the techniques for subduing the slave class,” is easy enough to parallel with Moore’s condemnation of his own education as a curriculum of “punctuality, obedience, and the acceptance of monotony,” just as his declaration that anarchist theories of education are based on “respect for the learner” parallels Moore’s observation that anarchism would require that people “be educated to a point where they were able to direct their own lives without interfering in the lives of other people.”

But ultimately, Moore, like Blake, is not one to lay out anything so banal as a singular policy proposal, or to endorse a specific ideology. Indeed, to do so would ultimately be contrary to what he was trying to accomplish. In numerous interviews, Moore has described the philosophical foundation of V for Vendetta as coming out of his belief that “the two poles of politics were not Left Wing or Right Wing. In fact they're just two ways of ordering an industrial society and we're fast moving beyond the industrial societies of the 19th and 20th centuries. It seemed to me the two more absolute extremes were anarchy and fascism.” And fascism’s central premise, as Moore puts it in V for Vendetta, is “strength in unity.” And so presenting a singular, clearly followable template of beliefs for others to follow would end up on the exact opposite end of the spectrum from where he wants to be. As he put it in a later interview, while talking about anarchy and fascism, “I don't necessarily want anybody to believe the same things I believe.” And Blake’s refusal to offer any straightforwardly positive alternative can be taken in largely the same vein.

Instead, anarchism can in many ways be described more as an aesthetic. Certainly that’s the sense that Moore gives at the start of “Fear of a Black Flag,” where he describes the associations of the word anarchy: “men in capes and broad-brimmed hats clutching black bowling balls with fizzing fuses and the helpful legend BOMB scrawled on the side in white emulsion,” “a Hieronymus Bosch landscape populated by looters, berserkers, giants with leaking boats for feet and eggshells for a body,” and “an ultra-violent and demented version of Spy vs. Spy, adapted from a screenplay by Rasputin and the Unabomber.” These are not ideological principles, but images, not unlike the quotations and movie posters that make up so much of V’s initial characterization.

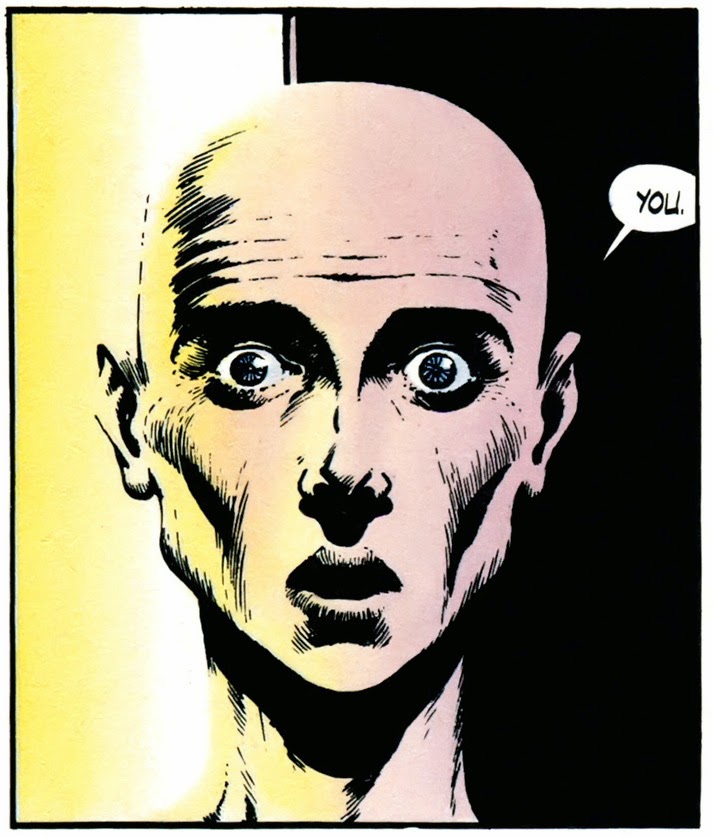

![]() |

Figure 616: The first page of Moore's essay

explaining the development of V for Vendetta. |

This highlights another key similarity between Europe a Prophecy and V for Vendetta, which is that both were eventually augmented with writers’ statements answering, as Moore puts in his (an essay entitled “Beyond the Painted Smile” that saw print in Warrior #17, the March 1984 issue of the magazine, between Chapters Five and Six of V for Vendetta, but written in October 1983, the month Chapter Two was published), the question asked “at every convention or comic mart or work-in or signing” by some “nervous and naive young novice,” namely “where do you get your ideas from?”

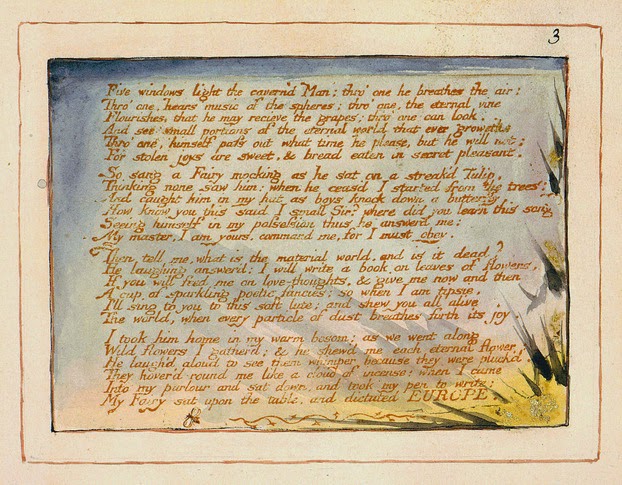

In Blake’s equivalent statement (a four-stanza poetic plate added as Object 3 to Europe a Prophecy Copy H, one of two copies made in 1795, a year after first publication, and retained in Copy K, the must lushly coloured of them, printed in 1821) he tells how “a Fairy mocking as he sat on a streak’d Tulip” attracted his attention by singing a song about how “Five windows light the cavern’d Man; thro’ one he breathes the air; / Thro’ one, hears music of the spheres; thro’ one, the eternal vine / Flourishes, that he may reieve the grapes; thro’ one can look. / And see small portions of the eternal world that ever groweth; / Thro’ one, himself pass out what time he please, but he will not; / For stolen joys are sweet, & bread eaten in secret pleasant.” Blake snuck up on the Fairy and caught him in his hat, thus binding the fairy to his service in the manner of such things.

![]() |

Figure 617: Blake's statement explaining the development

of Europe a Prophecy (Copy K, Object 3, written 1795, printed

1821) |

Blake then proceeded to ask the Fairy a rather idiosyncratic question: “what is the material world, and is it dead?” The Fairy laughed, and said, “I will write a book on leaves of flowers, / If you will feed me on love-thoughts, & give me now and then / A cup of sparkling poetic fancies; so when I am tipsie, / I’ll sing to you this soft lute; and shew you all alive / The world, when every particle of dust breathes forth its joy.” Blake obliged, gathering flowers as he walked with the Fairy, and as they did the Fairy showed him each one and “laugh’d aloud to see them whimper because they were pluck’d,” hanging around Blake “like a cloud of incense.” Blake went inside, took out a pen, and the “Fairy sat upon the table, and dictated EUROPE.” (When asked in 2014 whether this account was actually true, Blake sardonically replied, “as true as this answer is.”)

Moore’s explanation, on the other hand, is a detailed account of the collaborative process between himself and artist David Lloyd as they refined ideas for the 1930s mystery story commissioned by Dez Skinn for the forthcoming Warrior. And yet for all that this appears, on the surface, the simpler and more straightforward explanation, it is in another a far thornier one. Europe a Prophecy came wholly formed, dictated by a fairy, its entirety explicable by that one act, uncanny as it may be. But V for Vendetta had an enormously complex history that was the result of months of refining ideas and throwing new ones into the hopper. Moore mentions dozens of influences over the course of “Behind the Painted Smile,” each of which in turn has a branching root system of causes and influences, all of which exist alongside other sources to which V for Vendetta self-evidently owes considerable debt and their own webs of influences and precedents.

Nevertheless, the question of how this object came to be is unavoidable. It is, after all, one of the twin plastic smiles that form the bulk of Moore’s direct political impact upon the world. It is the work that would go on to be directly and consciously appropriated to provide a symbol employed by anarchist and countercultural protest groups on a global scale. It has a strong case, of all of the spells cast in the course of the War, of being the one that would go on to have the single greatest impact. And of the spells cast, it is the one whose influences are, perhaps, the purest. Its characters are original creations of Moore and Lloyd. For all the influences that exist, it is unlike, say, Moore’s run on Swamp Thing, where he worked primarily with existing creations. It also dates to such an early point in Moore’s career that it can legitimately be said to bear little to no influence from the rest of the War. The only major combatant to have done any work predating V for Vendetta is Morrison, whose work Moore almost certainly had not seen when he began work. Moore’s work was not yet informed by his growing sense of mistrust towards the comics industry - he was still nothing more than another jobbing freelancer trying to get out of a banal and dead-end job. V for Vendetta, in other words, is simply the product of two British men in their late twenties/early thirties who wanted to make a living doing comics. To understand anything that subsequently happened in the War, then, it is necessary to understand that process.

In Moore’s telling, as mentioned, it was very much David Lloyd’s idea to model V’s visual look upon Guy Fawkes, after spending some time trying more conventional designs. At the time Lloyd hit on the idea, the current idea was modeled after police uniforms (at the time it was thought V might have infiltrated the police force). As Moore describes it, “it had a big ‘V’ on the front formed from the belts and straps attached to the uniform, and while it looked nice, I think both Dave and I were uneasy about falling into such a straightforward super-hero cliché.” Certainly the Guy Fawkes image was more visually striking, but its import goes beyond that. Upon reading it, “all of the various fragments in my head suddenly fell into place, united behind the single image of a Guy Fawkes mask.” Clearly Lloyd had hit upon something substantial.

![]() |

Figure 618: Guy Fawkes as depicted by George

Cruikshank in an illustration for William Harrison

Ainsworth's Guy Fawkes; or, The Gunpowder

Treason (1841) |

And yet Guy Fawkes himself is hardly a promising figure for what Moore was trying to accomplish with V for Vendetta. Yes, he did notably try to blow up the Houses of Parliament, but his reasons for doing so and his larger plan are hardly ones Moore would sympathize with. Fawkes, simply put, was a militant Catholic who wanted to assassinate King James I and make England a Catholic nation again, undoing Henry VIII’s foundation of the Church of England. Fawkes converted to Catholicism in his teenage years following the death of his father and his mother’s remarriage to a Catholic, and in 1591, at the age of twenty-one, relocated to the continent, fighting for Spain in the Eighty Years War against the breakaway Dutch Republic. He was among the soldiers at the 1596 Siege of Calais, and by 1603 was being viewed as officer material. At this point he adopted the Italian equivalent of his name, rebranding himself Guido Fawkes, and traveled to Spain to seek King Philip III’s support for a Catholic rebellion in England following the 1603 ascension of King James and union of the Scottish and English Crowns.

![]() |

Figure 619: Guy Fawkes and his co-conspirators as depicted by Crispijn van

de Passe |

At this time the fines levied against practicing Catholics were a significant source of income for England, and James was emphatic in his denunciations of Catholics, especially after his discovery that the pope had secretly sent a rosary to his wife. The resulting crackdown included the expulsion of all Catholic priests from the country and a stepping up in enforcement of the fines, leading to considerable discontent among Catholics. Among those unhappy was Robert Catesby, who began recruiting co-conspirators for a plot against the king. Among the first of these was his cousin, Thomas Wintour, who traveled to Spain in early 1604, where he met Fawkes and recruited him into the plot, returning with him to England in April of 1604.

![]() |

Figure 620: Guy Fawkes being captured by Thomas Knyvet,

as depicted by Henry Perronet Briggs (1823) |

The core of Catesby’s plan was to blow up the Houses of Parliament during its opening, killing the bulk of Parliament and James I at the same time. This was to coincide with the incitement of a revolt in the Midlands, and with the kidnapping of the Princess Elizabeth, who lived in Warwick and was thus conveniently positioned for the Midlands-based conspirators to pop over and kidnap. Elizabeth was eventually to be installed on the throne to serve as a Catholic monarch. Fawkes, as the participant with the most military experience, was placed in charge of managing the explosives, which were steadily smuggled into a cellar beneath the Houses of Parliament. An outbreak of plague delayed the opening of Parliament from February 1605 to October, and then, subsequently, to the fifth of November, 1605. This, however, proved sufficient delay that an anonymous letter ended up tipping off James I to the conspiracy, and he tasked Lord Chamberlain Thomas Howard with conducting an exhaustive search of the Houses of Parliament. These uncovered Fawkes beside a pile of firewood, which he managed to explain away. A second search headed by Thomas Knyvet in the early hours of November 5th, however, uncovered Fawkes in his famous cloak and hat, and arrested him, foiling the plot.

It is not that this is entirely unsympathetic. Fawkes himself was a Catholic supremacist, but he fit into the same centuries-long tradition of religious dissidence in England that would eventually produce William Blake. And as David Lloyd noted, the basic cheek of trying to blow up Parliament is rather appealing.

.jpg)